Miscellanea is a series of articles that will be published individually and will be included in a single issue when a sufficient number of articles have been accepted for publication.

In her autobiography, Mary Church Terrell recounts an event that filled her with such pride, she felt as though she “had grown an inch taller.”1 In 1902, Prince Henry of Prussia, the grandson of Queen Victoria, visited the United States. Mary and Booker T. Washington were among the attendees at a reception held for the prince at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York City. During the event, the Prince asked to speak with Washington, and by all accounts, the encounter was a great success. The man who hosted the prince on behalf of US President Theodore Roosevelt described it in this way: “The ease with which Washington conducted himself was very striking. […] Indeed, Booker Washington’s manner was easier than that of almost any other man I saw meet the Prince in this country.”2 Mary Church Terrell viewed the meeting similarly.

Terrell was a social activist, working with Ida Wells on anti-lynching campaigns and collaborating with others to found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Association of Colored Women. What made her feel an inch taller was her reflection on their morning with the prince and Washington’s subsequent lunch hosted by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt. “Thus did an ex-slave [Washington] and one of his friends touch elbows and clasp hands with royalty, as represented by a monarchical government of Europe, and sit at the table of royalty, as represented by Republican America.”3 Terrell’s description of Washington fits well with the events of the following pages. He regularly interacted with ease with heads of state, for example, US president Theodore Roosevelt, and with other educational leaders, such as the first president of the University of Chicago, William Rainey Harper. In a brief exchange, Washington applied the same expert communication skills to a conversation about ancient Nubia with the US Egyptologist, James Henry Breasted.

This article outlines in broad strokes Booker T. Washington’s perspectives on education, which were shaped by his own educational experiences and the particular needs of the students who attended Tuskegee Institute, which he ran from 1881 until his death in 1915. His program of industrial education has often been distinguished from the liberal arts style of education championed by his contemporary W. E. B. Du Bois. In the following pages, we will see that their approaches were complementary, not contradictory, means of adapting and maneuvering within a system that was riddled with obstacles designed to hinder their students’ success. Washington’s awareness of an obstacle-ridden system is clear in his correspondence with Breasted who explicitly isolates Washington from the ancient Egyptian culture. But that was of no significance to Washington who, with his focus on industrial education, was uninterested in Breasted’s esoteric considerations of ancient Nile Valley cultures and who, in any case, viewed the ancient Egyptians as unjust persecutors. The research questions that interested Booker T. Washington were not those that interested most Egyptologists at that time, although they are increasingly of interest today to scholars, particularly in fields adjacent to Egyptology.

Washington found no benefit in Egyptological research for African descended people in the US. Nonetheless, this article points out a lesson drawn from his approach that is particularly urgent for our contemporary world. Scientific research has offered great benefits and also great pain and injustice, as clearly demonstrated in the decades-long syphilis study centered at Tuskegee that is now recognized as a textbook case of medical racism. Yet despite such unethical practices, we do not abandon scientific inquiry. Just as Washington weighed the benefits of Egyptology, we must interrogate the purposes and benefits of research questions to recognize when seemingly worthwhile studies actually result in harm.

1. Industrial and Liberal Arts Education¶

At the turn of the century in the United States, there was discussion in African American communities as to the best type of education that should be provided for African Americans. At a very basic level, the two sides of the dispute advocated either for industrial education or book-based learning. The two people often positioned as the figureheads advocating for each perspective were Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois, although their points of view were not as diametrically opposed to one another as they are sometimes presented.

Booker T. Washington was born in Virginia to an enslaved woman named Jane who, after emancipation, took him and her other two children to live with her husband in West Virginia.4 They lived in extreme poverty, and immediately he and his older brother worked in physically arduous conditions to help their stepfather provide for the family. When neighboring families chipped in to pay a teacher to instruct members of the community, he continued to work during the day and completed his schoolwork at nighttime.5 From such inauspicious beginnings, Washington was able to secure a college education for himself, and by his mid-twenties, he was appointed to lead a new school that would train African American teachers, what is today Tuskegee University in Alabama.

Washington framed the particular advantage of industrial education over so-called book learning in terms of its positive impact on the lives of White people. As he described it in a 1903 article in The Atlantic, Black professionals, such as lawyers, doctors, and ministers, primarily served Black communities, but Black people trained in trades and business pursuits could serve both Black and White communities.

There was general appreciation of the fact that the industrial education of the black people had direct, vital, and practical bearing upon the life of each white family in the South; while there was no such appreciation of the results of mere literary training. […] The minute it was seen that through industrial education the Negro youth was not only studying chemistry, but also how to apply the knowledge of chemistry to the enrichment of the soil, or to cooking, or to dairying, and that the student was being taught not only geometry and physics, but their application to blacksmithing, brickmaking, farming, and what not, then there began to appear for the first time a common bond between the two races and coöperation between North and South.6

Du Bois, on the other hand, felt that higher education should not be focused on teaching the skills necessary to earn a living, but should shape students into people by teaching them how to think.

Teach the workers to work and the thinkers to think. [...] And the final product of our training must be neither a psychologist nor a brickmason, but a man. And to make men, we must have ideals, broad, pure, and inspiring ends of living,—not sordid money-getting.7

Although it may seem as though differences in educational philosophy separate these men’s views, in fact each also supported the other’s vision. In 1902, Washington wrote about the goal of education in a way that sounds similar to Du Bois’s view, that education makes human beings: “The end of all education, whether of head or hand or heart, is to make an individual good, to make him useful, to make him powerful; is to give him goodness, usefulness and power in order that he may exert a helpful influence upon his fellows.”8 In December of the following year, Du Bois gave a lecture in Baltimore where he expressed his approval for industrial training as long as it did not threaten book-based learning: “A propaganda for industrial training is in itself a splendid and timely thing to which all intelligent men cry God speed. […] But when it is coupled by sneers at Negro colleges whose work made industrial schools possible […] then it becomes a movement you must choke to death or it will choke you.”9 Washington and Du Bois appreciated the value in the other’s perspective, but their strategies emphasized a different best path forward.

Washington and Du Bois formulated educational methodologies within systems that were not set up to benefit their targeted groups of students: people of color in the racially segregated United States. Each educator found ways to maneuver within that system, to carve out a space where their methodology might be successful without threatening the dominant (White) systems. Washington articulated his position in a speech he gave in Atlanta in 1906. He knew that people of color attaining education, wealth, and civil rights were seen by many White people as a threat to their own wealth and rights. Washington sought to allay those fears by assuring his audience that people of color had “no ambition to mingle socially with the white race. […] [or] dominate the white man in political matters.”10 Washington’s separatist vision was at odds with Du Bois’s vision of integration and was less challenging to White people who were wary of losing their own status in awarding social gains to people of color.11

Mary Church Terrell took a stance in the middle ground of this debate. She was born to a couple who had been formerly enslaved but achieved great financial success through their business ventures and were able to provide her with elite schooling. As an African American woman with a master’s degree in ancient Greek and Roman cultures from Oberlin College, she had experienced and benefitted from a liberal arts education.12 She also had great respect for the type of education that Washington facilitated through Tuskegee. Her concern was that Washington promoted that education to the exclusion of other types of education.

I was known as a disciple of the higher education, but I never failed to put myself on record as advocating industrial training also.

After I had seen Tuskegee with my own eyes I had a higher regard and a greater admiration for its founder than I had ever entertained before. […] From that day forth, whenever these friends tried to engage me in conversation about Tuskegee who knew that ‘way down deep in my heart I was a stickler for the higher education, and that if it came to a show down I would always vote on that side, I would simply say, “Have you seen Tuskegee? Have you been there? If you have not seen it for yourself, I will not discuss it with you till you do.”13

Washington saw his system of industrial education as the way to prepare African Americans to participate in the economic systems in the United States from which they had been excluded for so long.14

A key to understanding the differing educational views of Du Bois and Washington rests in their own family situations and educational experiences, as well as the experiences of the students whom each envisioned they would be serving. As mentioned earlier, Washington’s schooldays in West Virginia mostly consisted of him doing the schoolwork at night after a difficult day’s work at the salt furnace or in the coal mines of West Virginia.15 With a bit of support from members of his community, who gave a few cents here and a few cents there, he set out walking, hitchhiking, and working to pay for food until he reached Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), where he continued to work to pay tuition.16 After completing that program and more schooling at Wayland Seminary (now Virginia Union University), Washington was hired in 1881, at about the age of twenty-five, to be the first leader of Tuskegee Normal (Teachers’) and Industrial Institute in Alabama.

Du Bois was born and raised in a predominantly White town in Massachusetts. His tuition at Fisk University in Nashville was provided for him through donations from a number of Congregationalist churches, and scholarships largely paid his way through Harvard University.17 As he later described it, the aid came him almost effortlessly, “I needed money; scholarships and prizes fell into my lap.”18 With those experiences, as well as a stint abroad at the University of Berlin, Du Bois greatly benefitted from book-based learning, and he believed it provided the best educational tools for the next generation. He famously quarreled with Egyptologist Flinders Petrie because Petrie not only did not see the merits of book-based learning for modern Egyptians, he inexplicably felt it would harm them.19 Du Bois countered Western colonial attitudes in his engagement with Petrie and in his many publications that centered the Africanity of ancient Nile Valley cultures. Like Du Bois, Washington was aware of White and Western-centric views of antiquity. But he did not devote his energies to resisting such claims because Egyptology was completely irrelevant to his educational program.

Because of his educational experiences, Du Bois was familiar with the types of students who had access to elite educations. As Washington describes the students at Tuskegee, they were a world away from the students who attended Fisk and Harvard.

The students had come from homes where they had had no opportunities for lessons which would teach them how to care for their bodies. [...] We wanted to teach the students how to bathe; how to care for their teeth and clothing. We wanted to teach them what to eat, and how to eat it properly, and how to care for their rooms. Aside from this, we wanted to give them such a practical knowledge of some one industry, together with the spirit of industry, thrift, and economy, that they would be sure of knowing how to make a living after they had left us. We wanted to teach them to study actual things instead of mere books alone.20

Tuskegee had a very different purpose and mission than an institution like Fisk University that Du Bois attended or Atlanta University where Du Bois taught because Tuskegee served a different group of students. The adaptive strategies that Washington and Du Bois developed to facilitate their students’ success reflect the very different environments in which they operated.

Tuskegee Institute thrived under Washington’s leadership and continues through the present in its educational mission. Du Bois’s dream of a liberal arts style of education widely available to students of color continues in many institutions, despite the fact that his own educational trajectory took a different turn. After holding a few different teaching posts, Du Bois left the ranks of faculty and became editor of The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP. His program of education continued through that work and through the many books he published, arguably reaching a much larger audience than his university teaching did. Under Du Bois’s leadership, The Crisis experienced an exponential growth in circulation, increasing readership by more than 500% in the first year and again by more than 600% in the following seven years.21

2. The Presidents of Tuskegee Institute and the University of Chicago¶

Although Booker T. Washington’s industrial education was far removed from an elite liberal arts education, Washington nonetheless had a close association with the president of just such an institution. The University of Chicago has become famous for its particular style of instruction that emphasizes honing analytical skills as opposed to parroting opinions. That educational philosophy is rooted in the practices of its first president, William Rainey Harper. As a teacher, Harper was described as instructing his students not in “what to believe, but how to think.”22 Despite the clear differences in curricula, the industrial education offered at Tuskegee Institute found an ally in the University of Chicago.

William Rainey Harper was appointed president of the University of Chicago in 1891, a decade after Booker T. Washington took the helm at Tuskegee Institute. Harper was involved in a wide-range of educational pursuits from laying the groundwork for today’s junior college or community college to promoting the arts and crafts movement, which sought to counter the growing role of mechanization.23 For example, the Industrial Art League, a nonprofit formed in 1899, asserted “the educational value of the handicrafts” and valuing “quality of production as against mere cheapness.”24 The five-person executive committee of the Industrial Art League included Chicago architect Louis Sullivan and William Rainey Harper.

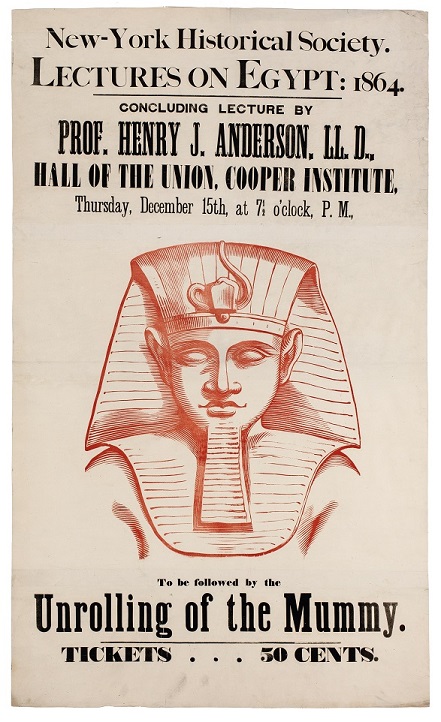

Washington and Harper became acquainted toward the end of the nineteenth century. Over the years, they had many opportunities to meet professionally. In 1895, Harper invited Washington to speak to the students of the University of Chicago. Washington recounted that he “was treated with great consideration and kindness by all of the officers of the University.”25 In October 1898, a National Peace Jubilee was held in Chicago following the end of the four-month Spanish-American War.26 Harper, in his role of chair of the committee on invitations and speakers, invited Washington to participate. The high-profile event was planned to be held over the course of many days, with intellectuals, social leaders, and war heroes speaking at various locations around Chicago. Dignitaries scheduled to attend included diplomats, members of Congress, and US president William McKinley.

On Sunday, October 16, Washington spoke to a huge crowd, reported to have numbered sixteen thousand. As he later wrote, it was “the largest audience that I have ever addressed,” including President McKinley.27 Washington gave a historical overview touching on the service of African Americans to their country and thanked the president, to wild acclaim, for recognizing their commitment to the United States during the war. Two days later, Washington spoke again, that time at Chicago’s Columbia Theater, a 600-seat venue, where he shared the stage with two esteemed veterans.28

In 1902, Harper was again instrumental in bringing Washington to speak in Chicago. The Industrial Art League, on whose executive committee Harper served, was building a new studio. US President Theodore Roosevelt did the honor of laying the cornerstone, and one of the invited speakers was Booker T. Washington.29

After Harper’s untimely death before his fiftieth birthday, in January 1906, Washington maintained his relationship with the University of Chicago through its next president, Harry Pratt Judson. In 1910, Judson invited Washington to speak on campus. His address in December of that year in Mandel Hall was entitled “The Progress of the American Negro.”30 A further connection between the University of Chicago and Tuskegee Institute was Julius Rosenwald, head of Sears, Roebuck and Company, who served on the Board of Trustees of both institutions.31 In February 1912, Rosenwald, Judson, and James R. Angell, Dean of the Faculties at Chicago, visited Tuskegee to see firsthand the work that Washington was doing. The visitors approved, stating that Tuskegee was “one of the most practicable and successful attempts to solve the Negro problem in the South.”32

In June 1912, six and half years after Harper’s death, the University of Chicago honored their first president by dedicating a library named for him. A large group of invited guests, including Booker T. Washington and other leaders in the world of higher education, as well as a crowd of about four thousand people listened to a series of addresses on topics such as the university’s libraries, its architecture, and the importance of literature (Fig. 1).33 The University of Chicago Magazine reported on Washington’s presence at the event in this way:

The delegates to the dedication to the Library numbered in all sixty. Among those to attract the greatest attention was the representative of Tuskegee Normal, Principal Booker T. Washington. Arriving late, he was the only man on the platform without a gown. This deficiency he supplied in the afternoon, however, without seeming to lessen the interest of the onlookers in his presence.34

The magazine’s remarks were reserved solely for Washington. No comment is made on the ceremony’s other attendees. Washington would surely not have read the article, which was aimed at a reading audience of graduates and other donors to the university. Nonetheless, the snide comments seem designed to embarrass him while simultaneously signaling the superiority of the other invited guests. The author objectifies Washington by viewing him as a curiosity.

![Booker T. Washington (far left) in procession to the afternoon Convocation at the University of Chicago, 1912. Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-08583, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library[^35] Booker T. Washington (far left) in procession to the afternoon Convocation at the University of Chicago, 1912. Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-08583, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library<sup id="657e8509e8c7674c8a16f298c2db3288fnref:35"><a href="#657e8509e8c7674c8a16f298c2db3288fn:35" class="footnote-ref" role="doc-noteref">35</a></sup>](../../images/BTW-Fig1.jpg)

Figure 1. Booker T. Washington (far left) in procession to the afternoon Convocation at the University of Chicago, 1912. Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-08583, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library35

Judson’s continuing relationship with Washington is interesting in light of Judson’s poor treatment of an African American student at the University of Chicago. Georgiana Simpson, who became the first African American woman to receive a PhD in the United States, was expelled from her campus dorm by Judson in 1907. Some White students complained about Simpson’s presence in the dorm, but the Dean of Women declared that Simpson would remain in her lodging. In a shocking display of micromanagement, Judson intervened in the matter and forced Simpson to move off campus. Thanks to the recent efforts of some undergraduates, a bust of Simpson commemorating her accomplishments now resides in the campus’s Reynolds Club opposite a plaque recognizing Judson.36 Judson’s treatment of Simpson in light of his relationship with Washington seems motivated by racism, sexism, and also a status differential, where Washington, as a fellow institutional head, was a peer, while Simpson was merely a student. Set against this complex backdrop, University of Chicago professor of Egyptology James Henry Breasted inserted himself in Washington’s world.

3. Ancient Nubia in The Biblical World¶

In December 1908, Breasted published an article in a journal called The Biblical World. In the article, he promoted his epigraphic work on “the monuments of the ancient kingdom of Ethiopia.”37 Like most scholars of that time, Breasted used the term Ethiopia to refer to the ancient culture of Nubia, not the modern country of Ethiopia. He also discussed various writing systems in ancient and modern Nubia and the recent acquisition of some ancient Nubian texts. The texts were written using Greek letters, but the language that lay underneath the letters was largely unknown to scholars. The content was Biblical in nature, and Breasted wrote with excitement about the possibility of deciphering the ancient language.

Breasted believed that the ancient language, once understood, would reveal connections between the scripts of the Nile River Valley’s lower area, most of modern-day Egypt, and its upper area, the southern part of modern-day Egypt and northern to central Sudan. He describes the ancient people of the Upper Nile as “neither pure negroes nor Egyptians,” with no explanation as to what either term means in a scientific sense.38 In the future, when their language would be deciphered, Breasted claimed that:

For the first time we shall then possess the history of an African negro dialect for some two thousand years; for while the Nubians are far from being of exclusively negro blood, yet their language is closely allied to that of certain tribes in Kordofan [Kurdufan in central Sudan] at the present day. In the Nubians, therefore, we have the link which connects Egypt with the peoples of inner Africa.39

Breasted’s racism tinged with colonialism is on full display in this section of the article. As he saw it, the ancient culture of the Lower Nile was “civilized” and the ancient culture of the Upper Nile was only civilized when it adopted Egyptian culture. Otherwise, the Upper Nile culture was doomed, in his view, to “barbarism.” “The Egyptian veneer slowly wore off as this kingdom of the upper Nile was more and more isolated from the civilization of the north, and it was thus thrown back upon the barbarism of inner Africa.”40

Breasted used imperialistic race-based language to describe the cultural influence that may have flowed from south to north, from “inner Africa,” as he put it, to the Lower Nile. “When, therefore, we are in a position to read the early Nubian inscriptions, we shall be able to compare the ancient Nubian with the Egyptian and thus to determine how far, if at all, the Egyptian language of the Pharaohs was tinctured by negro speech.”41 The word “tinctured” is associated with dyeing or coloring. Breasted drew a color line that separated the people who spoke the undeciphered language (“an African negro dialect”) and those who spoke the “language of the Pharaohs” (clearly “non-negro” in his view). When he wrote of the “coloring” influence of the language of the Upper Nile on the language of the Lower Nile, he revealed his US-American race-based perspective, drawn from his contemporary world. Then he incorrectly projected his contemporary Western worldview on to the world of the ancient Nile cultures that he studied. An increasing number of scholars are now devoting their publication efforts to correct colonialist attitudes of this type.42

4. Breasted Writes to Washington¶

Breasted was offered a career as a faculty member when he was still an undergraduate. Willian Rainey Harper was a professor at Yale when Breasted studied there. Harper was planning the new University of Chicago and learned of Breasted’s interest in the ancient Egyptian language. He encouraged Breasted to study it in Germany with the assurance that a job would be waiting for him in Chicago when he finished.43 By 1894, Breasted had completed his degree and was teaching Egyptology at the new university, establishing himself as one of the founders of the discipline in the US system of higher education.44

In late 1908, when Breasted’s article was published in The Biblical World, Washington had been head of Tuskegee Institute for nearly three decades. He was a leader in the fight for educational and labor rights for African Americans, an international figure who regularly interacted with heads of state and whose professional acquaintance was cultivated by other educational leaders like the presidents of the University of Chicago.

In April 1909, Breasted sent a copy of his article to Washington. In an accompanying letter, he wrote about his work on ancient Nile Valley cultures, and he described the article as being about “a matter concerning early history of your race.”45 Breasted once again demarcated “Nubian” from “Egyptian” and marked the former as belonging to African Americans, thus excluding them from the realm of ancient Egyptians.

In his letter to Washington, Breasted explained the importance of the decipherment of the ancient Nilotic language in this way:

The importance of all this is chiefly that from these documents when deciphered, we shall be able to put together the only surviving information on the early history of the dark race. Nowhere else in all the world is the early history of a dark race preserved.46

Again, Breasted expresses a segregationist viewpoint, where he imagines the inhabitants of the Upper Nile are members of a “dark race” as distinguished from the people whom he imagined in the Lower Nile. In the letter’s closing, he states that he mailed the article to Washington because “possibly one who has done so much to shape the modern history of your race will be interested in the recovery of some account of the only early negro or negroid kingdom of which we know anything.”47 The slipperiness of Breasted’s argument is clear. His letter declares the evidence to be of an “early negro or negroid kingdom,” “a dark race,” one that Washington shares, and in the article, he describes the people of the Upper Nile as “neither pure negroes nor Egyptians.”48 Breasted’s argument about race was based on unscientific terminology that lacked precise definitions and resulted in prejudiced and incorrect conclusions.49 The slipperiness of his arguments applies across his publications because, as we will see below, he expresses different views in different publications.

5. Washington’s Response and the Brownsville Affair¶

At the time that Breasted sent the article, Washington was preoccupied with something far removed from the arcane world of ancient Nilotic cultures. He was grappling with the aftermath of an injustice done to black soldiers stationed in Brownsville, Texas. At the time, the soldiers were deemed guilty without the benefit of having had their case heard through regular legal proceedings. US president Theodore Roosevelt refused to undo the damage to their reputations, careers, and futures. The US Army launched subsequent inquiry that concluded in 1972 that all of the accused people were innocent.50

Roosevelt and Washington were closely connected, as Washington advised Roosevelt on matters related to issues facing African American communities. Roosevelt became president following the assassination of President McKinley, two years after Washington had spoken before McKinley and the largest audience of his career at the peace jubilee in Chicago. About a month after taking office in 1901, Roosevelt invited Washington to dinner at the White House. The event, aimed at securing the support of African Americans for the new president, was also a recognition of the acceptability in some White circles of Washington’s philosophy of “self-help and accommodation of segregation.”51 Nonetheless, the dinner invitation caused an angry backlash among some White politicians and members of the press who were enraged by the honor given to Washington.52

Five years after that dinner, in November 1906, President Roosevelt publicly announced his decision to declare, without due process, that the African American soldiers at Brownsville were guilty of murder and conspiracy to hide murderers. Before the public announcement, Roosevelt relayed his decision to Washington who tried unsuccessfully to change the president’s mind.53 Mary Church Terrell was well placed enough to intercede with the Secretary of War William Howard Taft to get a brief stay of the president’s order.54 She saw a connection between the injustice to the soldiers and the White House dinner. “He [Roosevelt] might have thought by discharging three companies of colored soldiers without honor he would prove to the South he was not such a negrophile as he had appeared to be.”55 In the midst of this crisis, Washington received Breasted’s letter.

Despite the pressing nature of the aftermath of the injustice done to the Black soldiers, Washington replied to Breasted the following week, expressing his polite interest in the matter. He noted that although he had not had time to acquaint himself with the ancient history of the Nile Valley, he did mention a particular point of interest. He wrote that “the traditions of most of the peoples whom I have read, point to a distant place in the direction of ancient Ethiopia as the source from which they, at one time, received what civilization they still possess.”56 Washington wondered if that “distant place” and the subject matter of Breasted’s article could be one and the same. “Could it be possible that these civilizing influences had their sources in this ancient Ethiopian kingdom to which your article refers?”57

6. Washington and Egyptology¶

Washington’s correspondence with Breasted is a fascinating chapter in histories of Egyptology and Nubiology, a chapter that needs to be included in future histories of these disciplines.58 The study of ancient Nile Valley cultures never factored into Washington’s work, as they did in the intellectual work of many other African Americans, including Du Bois.59 There are obvious reasons why the topic would not resonate deeply with Washington.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many Egyptologists had largely agreed on a historical narrative that connected the northern Nile Valley—in what is today the country of Egypt—with the Levant, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and parts of the northern Mediterranean, while simultaneously isolating it from Arabia and parts of Africa to the south and the west.60 More than reflecting any historical reality, this one-sided isolation reflects the research interests of early Egyptologists, their sources of funding, which were often people or organizations interested in exploring sites associated with Biblical stories, and the predetermined worldview that researchers brought to the material.

In his letter to Breasted, Washington makes connections across Africa, between the southern Nile Valley and West Africa.61 Research questions like the one he posed (“Could it be possible that these civilizing influences had their sources in this ancient Ethiopian kingdom to which your article refers?”) continue to be of interest to scholars, although more so to scholars in fields adjacent to Egyptology.62 Washington does not challenge the divide that Breasted imagined between the northern and southern Nile Valley. His reticence to identify with the northern Nile Valley was rooted in an entirely different set of motivations.

As mentioned earlier, Washington was born into slavery. Because of his experience, the Biblical story of the Exodus resonated strongly with him. In one publication, he wrote, “I learned in slavery to compare the condition of the Negro with that of the Jews in bondage in Egypt, so I have frequently, since freedom, been compelled to compare the prejudice, even persecution, which the Jewish people have to face and overcome in different parts of the world with the disadvantages of the Negro in the US and elsewhere.”63 Where Breasted viewed the ancient Egyptian culture as a “great civilization,” Washington saw it as an unjust power that enslaved other people. Finally, Washington’s pedagogical system focused on industrial education. Undeciphered ancient texts from the southern Nile and the enslavers of the Jewish people in the northern Nile Valley had no place in his educational worldview. But although Washington never incorporated ancient Nile Valley cultures into his work, Breasted continued to produce incorrect arguments that attempted to divide the ancient Nile Valley along so-called racial lines.

7. Breasted on Race¶

Breasted wrote many books on the ancient cultures of Europe, Asia, and Africa for a general reading audience and for use in schools. His views on the ancient people of the Nile Valley are made clear in his 1935 school textbook Ancient Times, first published in 1916. In Ancient Times and the accompanying atlases, Breasted connects the ancient cultures of the Near East, as it was called, and Europe to illustrate the spread of “western civilization.”64 In Ancient Times, a map labels Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa as “Great White Race,” and the area to the south of that is labeled “Black Race.”65 Breasted does not provide a formal definition of race, and he sometimes treats race as though it is tied to language or culture (both incorrect ideas).66 His muddled discussion sometimes suggests that race is a well-defined category with strict boundaries, and other times his discussion blurs those boundaries.

Breasted’s ideas about race are incorrect by the scientific standards of today and even of his own day. Anthropologist Franz Boas (1858–1942) offered an alternative anthropological view. “Put simply, Boas—albeit grudgingly—attempted to extricate race relations theory from most of the racist assumptions of late nineteenth-century social science.”67 Repeatedly in his work, Boas discussed variation, arguing that “human beings possessed enormously varied physiques, so diverse that what at first appeared to be easily bounded racial types turned out to grade into each other.”68 A racializing classification system, with its attempt to set firm boundaries delineating different groups of people, ignores the reality of variation in human populations.

The skeletal concept of “race” depended and depends on arbitrarily defined, well-marked anatomical complexes or “types” which had by definition little or no variation. However, modern population biology has demonstrated that variation with geographically defined breeding populations, or those more related by ancestry, is the rule for human groups.69

The confusion arises because variation in physical features became the basis for “race” and was used to classify humans, but humans defy classification because of variation.

Here the phrase “concept of race” refers to the biological idea as found in science texts in its most idealized form, namely that biological human population variation can be, or is to be partitioned into units of individuals who are nearly uniform, and that there is greater difference between these units than within them. This concept implies or suggests/emphasizes between-group discontinuity in origins, ancestral and descendant lineages, and molecular and physical traits, implying the opposite for within group variation. The human reality is different.70

Two people who may appear to be different based on physical features may not actually be different when examined at a genomic level. Furthermore, there are more similarities between human population groups than there are differences.

No such border (or color line), like the one that Breasted drew on the map, exists in reality. That becomes quite clear when considering where such a line would run.

There seems to be a problem in understanding that human genetic variation cannot always be easily described. Genetic origins can cut across ethnic (sociocultural or national) lines. At what village along the Nile valley today would one describe the “racial” transition between “Black” and “White”—assuming momentarily that these categories are real? It could not be done.71

Not only does such a line on a map not exist in reality, but the very idea of separating the Nile River Valley in the way that Breasted imagined is nowhere reflected in the ancient material. The “racialization of Nubia and Nubians as ‘black’ in contrast to Egyptians [is incorrect], implying an essentialized racial divide between Egypt and Nubia that would not have been acknowledged in antiquity.”72 Because the material record does not provide the separation that Breasted’s theory requires, he had to resort to an inaccurate description of the geography. He argues that the culture in the northern Nile Valley was isolated from the rest of the landmass. Breasted incorrectly describes the Nile River Valley in this way:

It [his area labeled “Black Race”] was separated from the Great White Race by the broad stretch of the Sahara Desert. The valley of the Nile was the only road leading across the Sahara from south to north. Sometimes the blacks of inner Africa did wander along this road into Egypt, but they came only in small groups. Thus cut off by the desert barrier and living by themselves, they remained uninfluenced by civilization from the north.73

This incorrect characterization ignores the fact that the area now known as the Sahara was not always a desert and ignores the existence of oases that continue in the present to facilitate movement across dry areas.74 Breasted himself makes that point in an earlier publication when he describes the desert around the Nile River Valley. “Plenteous rains, now no longer known there, rendered it a fertile and productive region.”75 In that case, he used the disciplinary boundaries set up by the university to separate those ancient people from the ones he studied. For him, humans living in the Nile Valley area in the Paleolithic “can not be connected in any way with the historic or prehistoric civilization of the Egyptians, and they fall exclusively within the province of the geologist and anthropologist.”76 With that comment, Breasted dispenses of any evidence that predates the era he wants to discuss, namely, predynastic and dynastic Egypt. Having dismissed that evidence, Breasted then incorrectly contrasts a “civilized” lower Nile Valley and a “barbaric” upper Nile Valley, a contrast that reflects more about the world of his day than the ancient world he imagined he was describing. As Stuart Tyson Smith put it:

The implied contrast between primitive and barbaric Nubians conquering their more sophisticated northern neighbor serves to reproduce and perpetuate a colonial and ultimately racist perspective that justified the authority of modern Western empires, in this case over “black” Africa, whose peoples could not create or maintain “civilized” life without help from an external power.77

Breasted’s segregation of the Nile Valley based on an nonexistent color line was founded on the mistaken idea that differences in physical appearance among humans correspond with differences in language or culture. That simply is not true, nor is it true that differences in the human genome correspond to linguistic or cultural differences.78

Breasted’s conception of races rested on many incorrect ideas, two of which I will touch on here. Breasted’s discussion intimates that there is such a thing as a “pure” race, meaning, a group of people who are so isolated from other people that they have bred only with each other since the beginning of time.79 Knowledge of human migrations easily disproves such an outdated concept.80 At a more local level, evidence to the contrary is easily seen within families, when certain traits are expressed or not expressed in various family members.

Defining a population as a narrow “type” logically leads to procedures such as picking out individuals with a given external phenotype and seeing them as members of a “pure race” whose members all had the same characteristics. This would imply that the blond in a family of brunettes was somehow more related to other blonds (“Nordics”) than to immediate family members.81

Breasted himself evidently realized that point. In his 1905 book A History of Egypt, he describes the ancient Egyptians in a way that belies the strict border delineated on his map. The book would be republished in a second edition just two years after the passage cited above and would be unchanged from the original edition, indicating that Breasted continued to hold to this view in the late 1930s.

Again the representations of the early Puntites, or Somali people, on the Egyptian monuments, show striking resemblances to the Egyptians themselves. […] The conclusion once maintained by some historians, that the Egyptian was of African negro origin, is now refuted; and evidently indicated that at most he may have been slightly tinctured with negro blood, in addition to the other ethnic elements already mentioned.82

Breasted’s dismissal of an “African negro” origin of Egyptians aligns with his racializing map in Ancient Times. But in the description above, he allows (again using the word “tinctured”) for some “negro blood” in the Egyptian population. By the standards of the US society in which Breasted lived, such an allowance would discount Egyptians from being White.

In his map, Breasted mistakenly depicted race as existing according to strict geographical boundaries, and in the passage above, he blurred that strict boundary line. The fuzziness of his racialized dividing line in the Nile Valley brings to mind Bernasconi’s interpretation of race as “a border concept, a dynamic concept whose core lies not at its center but at its edges and whose logic is constantly being reworked as the borders shift.”83 Bernasconi argues that in the United States, race should be seen as a “fluid system that never succeeded in maintaining the borders it tried to establish, but whose resilience came from the capacity of the dominant class within the system to turn a blind eye to their inability to police those boundaries effectively.”84 The idea of race as a fluid system can be seen in these ideas of Breasted’s. One of the discipline’s founders literally drew a color line across the Nile Valley (the map) even when by his own account (the text quoted above) people’s features blurred that line due to what he called “ethnic elements” among Egyptians. On a macro scale, the discipline of Egyptology in the US did the same. Despite the fact that one of the discipline’s founders made these statements, the discipline continues to “turn a blind eye,” having distanced itself from the statement without formally acknowledging its role in promoting such racist ideas.

Breasted’s second incorrect idea is his failure to explain how early humans who settled in Europe became “White.” His narrative makes it seem as though they simply appeared in Europe, already White.85 To account for Egypt’s place in a sphere dominated by “Europe” and described by him as “White,” Breasted produces a convoluted argument that ignores the very evidence that he has laid before the reader. “In North Africa these people were dark-skinned, but nevertheless physically they belong to the Great White Race.”86 With that illogical statement, Breasted opens the doors of his “Great White Race” to “dark-skinned” people. What then closes the doors to other dark-skinned people, such as those who inhabited the space he labeled “Black Race”? The answer is found in Breasted’s view of “civilization,” which for him was very much a White, Western, male-dominated space, something that he incorrectly felt was off-limits to other parts of Africa.

8. Breasted on Civilization and Women¶

Western imperialism is on clear display in Breasted’s 1926 book, The Conquest of Civilization. The title of his book signals his evolutionary view of human sociocultural development. Reflecting on history, Breasted sees a “rising trail” that “culminated in civilized man,” and he repeatedly contrasts that trajectory with “bestial savagery,” the earlier state of humans.87 When Breasted referred in his book title to civilization as conquering, he was not speaking metaphorically. His narrative romanticizes “great men” carrying weapons. In his preface, Breasted gazes over the plain in present-day Israel where his Rockefeller-funded excavations occurred. He glowingly recalls the Egyptian king Sheshonq who raided Jerusalem in tenth century BCE and the 1918 victory of the English Lord Allenby over Ottoman forces.88 The types of actions that constituted civilization and civilized people, in Breasted’s view, included acts of violence, theft, invasion, and subjugation of others. Breasted does not question who comprises “mankind” or whether the “progress” that some modern humans had achieved positively impacted others.89

Breasted’s worldview was impacted by colonialism, sexism, and racism. In the first edition of his textbook Ancient Times, Breasted paints a negative picture of the women of early human history. He blames the loss of an idyllic male hunting fantasy on a physically overwhelmed “primitive woman.” “Agriculture […] exceeded the strength of the primitive woman, and the primitive man was obliged to give up more and more of his hunting freedom and devote himself to the field.”90

Breasted reveals a similar lack of regard for contemporary women in a letter to his patron, John D. Rockefeller. In the letter, Breasted thanked Rockefeller for his “delightful companionship” during the Rockefeller family’s visit to Egypt. The Egyptologist recounted with jocularity what must have been a spirited discussion one day.

On the important question of the relative value of men and women to human society, Mrs. Rockefeller and Mary were somewhat out-voted when it came to a show of hands; but Mrs. Rockefeller never lost a scrimmage; she gave as good as she got in a spirit of unfailing good humor and amiability that won all hearts.91

Whether Mrs. Rockefeller and Mary actually felt any type of good humor at being relegated to a place of less value to human society is not clear from this passage.

Over the course of his career, the Rockefeller family repeatedly provided funds to enable Breasted’s work along the Nile and in the Middle East. One such notable case was in an ill-fated museum to be built in Egypt.92 Breasted used an imperialistic appeal to stress the grand implications of his work. He wrote to Mrs. Rockefeller that the museum was “not really business, but the fate of a great civilization mission, sent out by a great American possessing both the power of wealth and the power of vision that discloses and discerns new and untried possibilities of good.”93 He composed the letter to Mrs. Rockefeller partially as an apology for the public uproar over the ultimately rejected proposal for the new museum.94 His imperialistic narrative takes a decidedly Christian turn when he refers to the plan to build the museum in Egypt as a “new Crusade to the Orient.”95 According to Breasted, the misunderstanding about Rockefeller’s intentions in building the museum were a result of the Egyptian public’s unawareness that the money was to be without any reciprocal return, but simply for the general good. In fact, a combination of factors doomed the plan, including a growing dissatisfaction with such imperialist actions and the fact that under the plan, the Egyptian Antiquities Service would cede control of the museum’s antiquities and all future antiquities found in Egypt for thirty-three years.96 Had the museum come to pass, Breasted and those involved in the museum would have defined, on Egyptian soil, what Egyptology would be in terms of its artifacts, practitioners, and historical narratives.

9. Research for Whose Benefit?¶

The point was made earlier that despite the fascinating exchange of letters between Booker T. Washington and James Henry Breasted, ancient Nile Valley cultures did not factor into Washington’s work although other African American intellectuals did write about them. With Washington, we see the importance of interrogating benefit. Who constructs the research questions, and whom does research benefit? The fact that Breasted did not have to ask such questions is evidence of his privilege. Breasted did not have to be concerned with who benefitted from his research and from the research of other Egyptologists. He knew that it benefitted people like him: educated men in the west who were considered White. (Egyptian men were not included in that category as evidenced in the story about the failed museum in Cairo that excluded them.) Booker T. Washington did need to ask that question. In the case of Tuskegee Institute, how would Egyptology (Nubiology as such did not exist then nor were academic silos as limiting–e.g., George Reisner’s move from Semitic languages to archaeology) benefit the African American students whom Washington was educating? His answer: It would not.

In fact, Tuskegee has unfortunately become a central word in making sure that harm is not done to people through research. The Tuskegee Experiment is the informal name of a decades-long deception and health crisis that the United States government foisted on innocent African American people.97 The research began as a health survey in rural areas where people lacked access to regular medical care. The survey, which was organized by federal and local public health professionals with funding from the Rosenwald Fund, tested people for syphilis. Rosenwald, it will be remembered, was a longtime benefactor of the University of Chicago and Tuskegee Institute. In 1932, the survey turned into a four-decade long program that purported to treat syphilis in African American men but instead purposefully did not do so because it instead secretly studied the effects of untreated syphilis.98

One outcome of the disastrous Tuskegee Syphilis Study was the creation of the Belmont Report. Written by the (US) National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research and released in 1979, the Belmont Report lays out ethical guidelines that continue to govern human subjects research in the US.99 It provides three principles that guide ethical questions that arise during research: respect for persons (including protecting those who are most vulnerable), beneficence (the obligation to not harm and to maximize benefits while minimizing harm), and justice (who benefits from the research and is burdened by it). The commission’s task—to revisit the exploitation of humans as subjects of research and to redress that history through policy—is an example of the “healing” that has recently been discussed as a goal within Nubian archaeology.100

Washington was not involved in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. He died in 1915, about fourteen years before the survey began. But this injustice was done in the county where Tuskegee Institute is located with the cooperation of many people in that community, including Tuskegee’s then-president.101 Whatever the reasons for those people’s cooperation, whether they even knew about the true nature of the so-called study, the lasting health and psychological impacts of the study are a grim reminder of the need to ensure the safety of human subjects in research. One step in that process is to analyze research questions to determine who will benefit.

Kim TallBear asks a similar question today. Her work shows the urgency in continuing to interrogate innovation to determine who systems are set up to benefit and what ramifications may be lying beneath the surface, unstated. Breasted’s theories about a “Great White Race” are thoroughly discredited. Also discredited are the racial typologies of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that some Egyptologists, like Breasted, used in their work. But the kernels of those ideas are beginning to make a comeback in the guise of DNA studies.

On the surface, DNA studies may seem to be of positive benefit to a community. As TallBear states, “It has become a standard claim of human-population genetics that this scientific field can save us from the evils of racism.”102 But she cautions that it is not that simple. “The science does not undermine race and thus racism, but it helps reconfigure both race and indigeneity as genetic categories.”103 In terms of ancient Nile Valley cultures, we have seen vast overstatements, where, for example, the genetic map of one or two individuals has been wielded as a marker of an entire population group spanning thousands of years and hundreds of kilometers with no attention paid to cultural context, human migrations, or variation among humans.104 Such overly broad claims based on a fraction of evidence completely disregard the complexities of human culture and seem to suggest that culture is written in human DNA, which is incorrect.105

The threat to people who participate in such studies involves loss of sovereignty over one’s genetic material, one’s personal narrative, and perhaps material assets as well. The worry is that DNA mapping projects are not concerned with the research subjects’ well-being but are solely done “to satisfy the curiosity of Western scientists.”106 The alarms that TallBear sounds are often muffled beneath rhetoric that sounds positive and promising, such as the idea that all humans originated in Africa and so are all “related.”

Privileging the idea that ‘we are all related’ might be antiracist and all-inclusive in one context, although that is also complicated, because it relies on portraying Africa and Africans as primordial, as the source of all of us. ‘We are all related’ is also inadequate to understanding how indigenous peoples reckon relationships in more complicated ways, both biologically and culturally, at group levels. ‘We are all related’ can also put at risk assertions of indigenous identity and indigenous legal rights.107

The cultural identification, what TallBear describes as being “at group levels,” is also missing from studies of ancient human remains in the Nile Valley. As Keita put it:

It is important to emphasize that, while the biology changed with increasing local social complexity, the ethnicity of Niloto-Saharo-Sudanese origins did not change. The cultural morays [sic], ritual formulae, and symbols used in writing, as far as can be ascertained, remained true to their southern [i.e., Egyptian] origins.108

In formal Egyptian artistic contexts, phenotype, along with dress and hairstyle, was used to represent groups of people according to ethnic stereotypes and then to characterize those ethnic groups in positive or negative ways, depending on official state ideology.109 The Egyptians’ highly stereotyped artistic representations of ethnic groups tell us only about the Egyptian ideology of ethnic distinctions, not about actual differences between ethnic groups. But even in the fantastical scenario that the ancient Egyptian portrayals were accurate, it would be impossible to map genotypical distinctions onto those ethnic groups. “One’s known ethnically identified ancestors and one’s genes ancestors are conceptually two different things.”110 Genotype, of course, had no bearing on a person’s “insider” or “outsider” status in ancient Egypt, regardless of whatever ethnic divisions existed among ancient peoples.111 TallBear has spent much time analyzing the impact and potential threats to Native American communities from research projects that want to study their genetic map, that claim to be able to tell them “who they are,” as if they did not know. Her grave concern for whom those studies benefit are a modern-day mirror to the racial typologies of the ancient Nile Valley that Booker T. Washington ignored.

TallBear’s warning to carefully consider the promises and the purposes of research is a first step in constructing a critical framework to examine Egyptological research. It is beyond the scope of this article to directly address the following issues, but their complexities should also be kept in mind. As mentioned above, a growing body of work addresses legacies of colonialism in the discipline of Egyptology.112 Alongside those works should be considered issues such as color prejudice in modern Egypt, the rights of indigenous people to a land’s history, and the particular challenges faced by African descended people in the US versus in Africa.113

10. Conclusion¶

Mary Church Terrell recalled with pride the day that Booker T. Washington met Prince Henry of Prussia in the morning and Mrs. Vanderbilt in the afternoon. Although some African descended scholars, such as W. E. B. Du Bois, are much feted in academic circles these days, Booker T. Washington is too frequently overlooked not only as a pioneer in education but in teaching students how to recognize what benefits them. Put in the language of the Harper and Breasted’s University of Chicago, he taught the students of Tuskegee how to think.

Washington felt his method of education could teach “self-help, and self-reliance,” as well as “valuable lessons for the future.”114 In the Institute’s early days, he had students constructing buildings and clearing land for agricultural purposes.

My plan was to have them, while performing this service, taught the latest and best methods of labour, so that the school would not only get the benefit of their efforts, but the students themselves would be taught to see not only utility in labour, but beauty and dignity; would be taught, in fact, how to lift labour up from mere drudgery and toil, and would learn to love work for its own sake.115

Despite the fact that the Institute and its community were the direct and visible beneficiaries of this labor, many students were nonetheless reluctant to do the work. Washington convinced the students at Tuskegee Institute of the benefit of his style of education by participating in the educational experiment with them.

When I explained my plan to the young men, I noticed that they did not seem to take to it very kindly. It was hard for them to see the connection between clearing land and an education. Besides, many of them had been school-teachers, and they questioned whether or not clearing land would be in keeping with their dignity. In order to relieve them from any embarrassment, each afternoon after school I took my axe and led the way to the woods. When they saw that I was not afraid or ashamed to work, they began to assist with more enthusiasm. We kept at the work each afternoon, until we had cleared about twenty acres and had planted a crop.116

Their labor on the grounds of the new Institute benefitted them as an educational community. As quoted early in this article, Washington also published an article in The Atlantic that framed such work as a benefit to White society. Why? Because Washington knew how to think from a position of precarity. He knew that the economic and social success of African Americans would begin to make White people feel that same precarity, a precarity usually only felt by people of color and the most economically disadvantaged White people. His piece in The Atlantic forestalled any such alarm in wealthier White circles by assuring them that the labor of African Americans benefitted White people too.

Washington found no benefit in Egyptology. Personally, he did not connect with the ancient culture. As a formerly enslaved person, he saw the ancient Egyptians through the lens of the Biblical Exodus, as those who enslaved other people. Systemically, there was nothing in Egyptology to benefit his educational system. Breasted’s “Great White Race” clearly excluded Tuskegee Institute. But Washington deftly shows us a way to move past the roadblock of Breasted’s Egyptology.

As seen in Washington’s interactions with world leaders and other university leaders, he handled difficult situations with ease. The same is true in his correspondence with Breasted. In his reply, Washington showed himself to be an astute reader, able to discern where in Breasted’s narrative he felt the benefit lay for African American communities. He sidestepped the contradictory narrative of the Nile Valley based on skin color and instead wrote an empowering narrative. He turned to the kingdom of the Upper Nile as an ancient source for the cultures of West Africa, where many African Americans traced their heritage.

As one of the founders of Egyptology in the US, Breasted’s viewpoints formed the basis of the discipline. His core values, with their attendant racist, sexist, and colonialist overtones, are clearly spelled out in public and in private, in the school textbooks and in the personal correspondence that he authored. To move away from those viewpoints and the unwelcome baggage they bring with them, Egyptologists must find alternative directions to the ones set out by early scholars like Breasted. One alternative path was offered by Booker T. Washington who considered cultural connections across Africa. Other scholars, in Africa and elsewhere in the world, have thought similarly. Increasingly, we see efforts to bring new perspectives to research questions in the Nile Valley and to make connections between the ancient Nile Valley and elsewhere in Africa. Washington modeled for his students a connection between physical labor and school education. In his brief encounter with Egyptology, he models for us a way to move forward from the discipline’s colonial outlooks.

11. Bibliography¶

Abd el-Gawad, Heba, and Alice Stevenson. “Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage: Multi-directional Storytelling through Comic Art.” Journal of Social Archaeology 21, no. 1 (2021): pp. 121–145. www⁄https://doi.org/10.1177/146960532199292

Abt, Jeffrey. American Egyptologist: The Life of James Henry Breasted and the Creation of His Oriental Institute. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

———. “Toward a Historian’s Laboratory: The Breasted-Rockefeller Museum Projects in Egypt, Palestine, and America.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 33 (1996): pp. 173–194.

Ambridge, Lindsay J. “History and Narrative in a Changing Society: James Henry Breasted and the Writing of Ancient Egyptian History in Early Twentieth Century America.” PhD diss. University of Michigan, 2010.

———. “Imperialism and Racial Geography in James Henry Breasted’s Ancient Times, a History of the Early World.” Journal of Egyptian History 5 (2012): pp. 12–33.

Ashby, Solange, and Talawa Adodo. “Nubia as a Place of Refuge: Nile Valley Resistance against Foreign Invasion.” In New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia, edited by Solange Ashby and Aaron Brody. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, forthcoming.

Asociación ANDES. “ANDES Communiqué, May 2011: Genographic Project Hunts the Last Incas.” May 14, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2022. www⁄https://www.slideshare.net/BUENOBUONOGOOD/andes-communique-genographicprojecthuntsthelastincas.

Baker, Shamim M., Otis W. Brawley, and Leonard S. Marks. “Effects of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, 1932 to 1972: A Closure Comes to the Tuskegee Study, 2004.” Urology 65,6 (2005): pp. 1259–62. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.023.

Baker, Lieutenant Colonel (ret.) William. The Brownsville Texas Incident of 1906: The True and Tragic Story of a Black Battalion’s Wrongful Disgrace and Ultimate Redemption. Fort Smith, AR: Red Engine Press, 2020.

Beatty, Mario H. and Vanessa Davies. “African Americans and the Study of Ancient Egypt.” forthcoming.

Bednarski, Andrew, Aidan Dodson, and Salima Ikram. A History of World Egyptology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Bernasconi, Robert. “Black Skin, White Skulls: The Nineteenth Century Debate over the Racial Identity of the Ancient Egyptians.” Parallax 13 (2007): pp. 6–20.

———. “Crossed Lines in the Racialization Process: Race as a Border Concept.” Research in Phenomenology 42 (2012): pp. 206–28.

Bieze, Michael. Booker T. Washington and the Art of Self-representation. New York: Peter Lang, 2008.

Bieze, Michael Scott and Marybeth Gasman, eds. Booker T. Washington Rediscovered. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Breasted, James Henry. Directors Correspondence. Records. Oriental Institute Museum Archives of the University of Chicago.

———. A History of Egypt. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905.

———. Ancient Times: A History of the Early World. Boston: Ginn and Company, 1916.

———. Ancient Times: A History of the Early World. 2nd ed. Boston: Ginn and Company, [1916] 1935.

———. “Recovery and Decipherment of the Monuments of Ancient Ethiopia.” The Biblical World 32.6 (Dec 1908): pp. 370, 376–385.

———. The Conquest of Civilization. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1926.

Breasted, James H., and Carl F. Huth, Jr. A Teacher’s Manual Accompanying the Breasted-Huth Ancient History Maps. Chicago: Denoyer-Geppert Company, 1918.

Buzon, Michele R., Stuart Tyson Smith, and Antonio Simonetti. “Entanglement and the Formation of the Ancient Nubian Napatan State.” American Anthropologist 118,2 (2016): pp. 284–300.

Capo Chichi, Sandro. “On the Relationship between Meroitic and Nigerian Aegides.” In New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia, edited by Solange Ashby and Aaron Brody. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, forthcoming.

Challis, Debbie. The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Davies, Vanessa. “Egypt and Egyptology in the Pan-African Discourse of Marcus and Amy Jacques Garvey.” Mare Nostrum 13,1 (2022): pp. 147–178.

———. “Pauline Hopkins’ Literary Egyptology.” Journal of Egyptian History 14 (2021): pp. 127–44.

———. Peace in Ancient Egypt. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

———. “W. E. B. Du Bois, a new voice in Egyptology’s disciplinary history.” ANKH: Revue d’égyptologie et des civilisations africaines 28/29 (2019–2020): pp. 18–29.

Dawood, Azra. “Building Protestant Modernism: John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Architecture of an American Internationalism (1919–1939).” PhD diss. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2018.

———. “Failure to Engage: The Breasted-Rockefeller Gift of a New Egyptian Museum and Research Institute at Cairo (1926).” MA thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010

Doyon, Wendy. “On Archaeological Labor in Modern Egypt.” In Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary Measures, edited by William Carruthers, pp. 141–156. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 1868–1963 (MS 312). Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center. UMass Amherst Libraries.

———. Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920.

———. “Lecture in Baltimore (December 1903).” In Against Racism: Unpublished Essays, Papers, Addresses, 1887–1961, edited by Herbert Aptheker, pp. 74–77. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1985.

———. The Autobiography of W. E. B. DuBois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century. (n.p.): International Publishers, [1968] 2003.

———. The Souls of Black Folk. 1903. With introduction by Ibram X. Kendi and notes by Monica M. Elbert. Reprint, New York: Penguin, 2018.

European History Atlas: Student Edition. Ancient, Medieval and Modern European and World History. Teacher’s Manual Accompanying the Breasted-Huth Ancient History Maps. Adapted from the large wall maps edited by James Henry Breasted and Carl F. Huth, and Samuel Bannister Harding. Chicago: Denoyer-Geppert Company, 1967.

Faraji, Salim. The Roots of Nubian Christianity Uncovered. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2012.

Feiler, Andrew. A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021.

Gatto, Maria Carmela. “The Nubian Pastoral Culture as Link between Egypt and Africa: A View from the Archaeological Record.” In Egypt in its African Context: Proceedings of the conference held at The Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009, edited by Karen Exell, pp. 21–29. Oxford: Archeopress, 2011.

Goodspeed, Thomas Wakefield. William Rainey Harper: First President of the University of Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1928.

Gourdine, Jean-Philippe, Shomarka O. Y. Keita, Jean-Luc Gourdine, and Alain Anselin. “Ancient Egyptian Genomes from Northern Egypt: Further Discussion.” ANKH: Revue d’égyptologie et des civilisations africaines 28/29 (2019–2020): pp. 155–161.

Gray, Fred D. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: The Real Story and Beyond. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2013.

Haley, Shelley P. “Black Feminist Thought and Classics: Re-membering, Re-claiming, Re-empowering.” In Feminist Theory and the Classics, edited by Nancy Rabinowitz and Amy Richlin, pp. 23–43. New York: Routledge, 1993. www⁄https://pressbooks.claremont.edu/clas112pomonavalentine/chapter/haley-shelley-1993-black-feminist-thought-and-classics-re-membering-re-claiming-re-empowering-in-feminist-theory-and-the-classics-edited-by-nancy-rabinowitz-and-amy-richlin-2.

Hall, Raymond L., ed. Black Separatism and Social Reality: Rhetoric and Reason. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon, 1977.

Hansberry, William Leo. Pillars in Ethiopian History: The William Leo Hansberry African History Notebook. Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1974.

Harlan, Louis R., ed. The Booker T. Washington Papers, Volume 1: The Autobiographical Writings. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972.

———. The Booker T. Washington Papers, Volume 4: 1895–98. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975.

Harper, William Rainey. The Trend in Higher Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1905.

Hassan, Fekri. “The African Dimension of Egyptian Origins.” Nile Valley Collective website. May 11, 2021. www⁄https://nilevalleycollective.org/african-dimension-of-egyptian-origins

———. “Memorabilia: Archaeological Materiality and National Identity in Egypt.” In Archaeology under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, edited by Lynn Meskell, pp. 200–216. New York: Routledge, 1998. www⁄https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203029817.

Heard, Debora D. “The Barbarians at the Gate: The Early Historiographic Battle to Define the Role of Kush in World History.” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35 (2022): pp. 68–92.

Jaggs, Andrew. “Maat - Iwa. Affinities between Yoruba and Kemet in the divine realm and ritual of the God-King, within the context of the Niger and Nile.” PhD diss. University College London, 2020.

Keita, S. O. Y. “Ancient Egyptian ‘Origins’ and ‘Identity’: An Etic Perspective.” Forthcoming.

———. “Ideas about ‘Race’ in Nile Valley Histories: A Consideration of ‘Racial’ Paradigms in Recent Presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from ‘Black Pharaohs’ to Mummy Genomes.” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35 (2022): pp. 93–127.

———. “Mass Population Migration vs. Cultural Diffusion in Relationship to the Spread of Aspects of Southern Culture to Northern Egypt during the Latest Predynastic: A Bioanthropological Approach.” In Egypt at Its Origins 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference “Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt”, Vienna, 10th–15th September 2017, edited by E. Christiana Köhler, Nora Kuch, Friederike Junge, and Ann-Kathrin Jeske, pp. 323–39. OLA 303. Leuven: Peeters, 2021.

———. “Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships.” History in Africa 20 (1993): pp. 129–54.

Langer, Christian. “The Informal Colonialism of Egyptology: From the French Expedition to the Security State.” In Critical Epistemologies of Global Politics, edited by Marc Woons and Sebastian Weier. Bristol, England: E-International Relations Publications, 2017. www⁄https://www.e-ir.info/publication/critical-epistemologies-of-global-politics.

Lemos, Rennan. “Beyond Cultural Entanglements: Experiencing the New Kingdom Colonization of Nubia ‘from Below.’” In New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia, edited by Solange Ashby and Aaron Brody. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, forthcoming.

———. “Can We Decolonize the Ancient Past? Bridging Postcolonial and Decolonial Theory in Sudanese and Nubian Archaeology.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2022): pp. 1–9. www⁄https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774322000178.

Lewis, David Levering. W. E. B. Du Bois: A Biography. New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2009.

Malvoisin, Annissa. “Geometry and Giraffes: The Cultural and Geographical Landscape of Meroitic Pottery.” Paper presented at the virtual Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt, 2020.

Minor, Elizabeth. “Decolonizing Reisner: A Case Study of a Classic Kerma Female Burial for Reinterpreting Early Nubian Archaeological Collections through Digital Archival Resources.” In Nubian Archaeology in the XXIst Century: Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference for Nubian Studies, Neuchâtel, 1st–6th September 2014, edited by Matthieu Honegger, pp. 251–262. Leuven: Peeters, 2018.

Monroe, Shayla. “Animals in the Kerma Afterlife: Animal Burials and Ritual at Abu Fatima Cemetery.” In New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia, edited by Solange Ashby and Aaron Brody. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, forthcoming.

Mudimbe, V. Y. The Invention of Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Rockefeller Archive Center.

Office of the Messrs. Rockefeller. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Rockefeller Archive Center.

Official Program of the National Peace Jubilee held at Chicago, Illinois, October 16–22, 1898. www⁄https://archive.org/details/officialprogram00nati/page/4/mode/2up.

Parsons, Geoffrey. The Stream of History. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1928.

Quirke, Stephen. “Exclusion of Egyptians in English-directed Archaeology 1882–1922 under British Occupation of Egypt.” In Ägyptologen und Ägyptologien zwischen Kaiserreich und Gründung der beiden deutschen Staaten, edited by Susanne Bickel, Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert, Antonio Loprieno, and Sebastian Richter, pp. 379–406. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2013.

Reid, Donald M. “Indigenous Egyptology: The Decolonization of a Profession?” Journal of the American Oriental Society 105, no. 2 (1985): pp. 233–246.

Riggs, Christina. “Colonial Visions: Egyptian Antiquities and Contested Histories in the Cairo Museum.” Museum Worlds 1, no. 1 (2013): pp. 65–84. www⁄https://doi.org/10.3167/armw.2013.010105.

Sabry, Islam Bara’ah. “Anti-blackness in Egypt: Between Stereotypes and Ridicule. An Examination on the History of Colorism and the Development of Anti-blackness in Egypt.” MA Thesis. Åbo Akademi University, 2021.

Schuenemann, Verena J. et al. “Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods.” Nature Communications 8, 15694 (May 2017). www⁄https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15694.

Scott, Emmett Jay, and Lyman Beecher Stowe. Booker T. Washington: Builder of a Civilization. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1916.

Smith, Stuart Tyson. “‘Backwater Puritans’? Racism, Egyptological Stereotypes, and Cosmopolitan Society at Kushite Tombos.” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35 (2022): pp. 190–217.

———. “Stranger in a Strange Land: Intersections of Egyptology and Science Fiction on the Set of Stargate.” Aegyptiaca, forthcoming.

———. Wretched Kush: Ethnic Identities and Boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire. London: Routledge, 2003.

Somet, Yoporeka. L’Égypte ancienne: Un système Africain du monde. Le Plessis-Trévise, France: Teham Éditions, 2018.

TallBear, Kim. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

———. “The Emergence, Politics, and Marketplace of Native American DNA.” In Routledge Handbook of Science, Technology, and Society, edited by Daniel Lee Kleinman and Kelly Moore, pp. 21–37. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2014.

Templeton, Alan R. “Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective.” American Anthropologist 100, no. 3 (1998): pp. 632–650.

Terrell, Mary Church. A Colored Woman in a White World. Reprint edition. Salem, NH: Ayer Company, 1986.

———. “Secretary Taft and the Negro Soldiers.” Independent 65 (July 23, 1908): pp. 189–190.

Teslow, Tracy. Constructing Race: The Science of Bodies and Cultures in American Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

The Daily Maroon. The University of Chicago Campus Publications. The Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center. University of Chicago Library.