1. Introduction¶

Gender studies in archaeology have moved a long way from the initial criticism of androcentrism (criticism of androcentric and heteronormative interpretations of the past, giving voices to ancient women, recognizing different genders behind the archaeological record), to viewing gender as a system or a result of performative practices.1 These developments in gender archaeology are not necessarily the same in all archaeological communities. In studies of ancient Sudan, gender studies have been introduced first through research of prehistoric and protohistoric societies2 and then through focus on Kushite royal women and the concept of queenship.3 The topic has been broadened by analyzing gender crossed with other aspects of identity, such as age, resulting in an intersectional understanding of identity in ancient Sudan.4 The focus in studies of ancient Sudan still seems to be largely on men (implicitly or explicitly), although recently, overviews on women, including non-royal women, have been published.5 Only few authors focused on masculinity.6 However, studies of gender are still far from being fully acknowledged in research on ancient Sudan. This is demonstrated by the lack of an entry on gender in even the most recent handbooks.7

In recent years, gender archaeologies are tackling a wide variety of different problems, offering equally varied approaches.8 Two related topics which have lately attracted the attention of several scholars are gendered violence and gender as a form of symbolic violence.9 Whereas scholars of the first search for evidence of quite specific gender patterns behind violent acts, scholars of the second argue that gender itself is a form of violence, because gender brings different people into asymmetrical relations of power in different domains. The idea that gender can be a form of symbolic violence is inherited from sociologist Pierre Bourdieu and philosopher Slavoj Žižek and has been only recently applied to archaeology.10 These discussions remind us that it is fruitful to think about gender from the point of view of violence, and to think about violence from the point of view of gender.

War is typically a sphere of past social action about which archaeologists and historians usually write from a male perspective and with the sole focus on men. The participation of women and their experiences are rarely addressed.11 War and violence in ancient Sudan are fields still largely dominated by male authors.12 This androcentric perspective rarely takes into account gender as a social category and tends to implicitly focus only on combatant men. As a result, we are left with numerous valuable contributions on Kushite representations of war, enemies, weaponry etc. However, a gender perspective is lacking in almost all of them. This does not mean that the effort to find women in such contexts or to relate these contexts to women is that which is lacking, although this is true too. What is missing, is a perspective on both masculinity and femininity as socio-culturally determined categories coming from a specific gender system. Until recently, this was also the case in Egyptology. However, some recent studies focusing on war in ancient Egypt have shown the potential of implementing ideas and concepts coming from gender studies.13 One of these concepts is the ‘frames of war’. The concept of the frames of war was developed by American philosopher Judith Butler, who demonstrated the way some political forces frame violence in modern media. Frames of war are operations of power which seek to contain, convey, and determine what is seen and what is real.14 They are the ways of selectively carving up experience as essential to the conduct of war.15 Butler argues that, by regulating perspective in addition to content, state authorities are clearly interested in controlling the visual modes of participation in war.16 The study by Butler on frames of war is essential for our understanding of how modern media creates the experience of war, whether and where they find a place for non-combatants, and how victory and defeat are presented. In this process, different genders are represented as differently positioned, depending on other identity categories such as age or status in an intersectional manner. According to Butler, we should undertake “a critique of the schemes by which state violence justifies itself”.17

In this paper, I will argue that gender was a frame of war that was also observable in the textual and visual media of ancient Sudan during the Napatan and Meroitic periods. I will first focus on non-combatants in texts, by analysing the attestations of prisoners of war of differing ages and genders. The lists of spoils of war demonstrate a structure based on a hierarchy based on status, age, and gender intersectionality. Intersectionality is one of the central tenets of black feminist theory. It is based on the fact that oppression is not monocausal, as for example in the USA it is not based either on race or on gender. Rather, an intersection of race and gender makes some individuals more oppressed or oppressed in a different way than others.18 This analysis of the attestations of non-combatants is followed by an analysis of a currently unique representation of women and children as prisoners of war found on the reliefs of Meroitic temple M250 in Meroe. After this, I turn to the feminization of enemies in Napatan and Merotic texts in order to demonstrate how gender was used to structure hierarchy and to position the Kushite king as masculine and his enemies as feminine. I argue that, in this way, gender framed both relations in war and hierarchies within the society of ancient Sudan. I also discuss evidence for the participation of Kushite royal women in war and stress that the sources at our disposal are providing us with an outsider (Graeco-Roman) perspective rather than a local perspective. Finally, I discuss the specifics of scenes in which Meroitic royal women are smiting enemies by comparing these scenes to others from ancient Egypt. I argue that the observed differences relate to a different understanding of the relation between kingship and queenship in these two societies.

2. Men, Women and Children as Prisoners of War¶

2.1. Textual Evidence¶

The taking of prisoners of war is a well-attested ancient war practice.19 Enemies of different gender, age, and status were also imprisoned during war in ancient Nubia. Although the practice surely must have been older, the first textual attestations come from the reign of Taharqa (690-664 BCE), and continue until the Meroitic period. The mentioning of men, women, and children as prisoners of war is mostly part of the lists of spoils of war. Since there is no space in this paper to thoroughly analyze these lists and present them in a systematic manner, I will concentrate only on prisoners of war, and especially on women and children, since they are often entirely neglected.20

The Kawa III stela of Taharqa (Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Æ.I.N. 1707, Columns 22-23) informs us that the king provided the temple of Amun with male and female servants, and the children of the rulers (ḥḳ3.w) of Tjehenu (Libyans).21 The Kawa VI (Khartoum SNM 2679, line 20-21) stela informs us that the temple of Amun in Kawa was filled with, among other others, female servants, wives of the rulers of Lower Egypt (T3-mḥw), and the children of the rulers of every foreign land.22 A granite stela from Karnak (line 3), attributed to Taharqa by Donald B. Redford, also mentions children of rulers, and later (lines 11-13) refers to the settling of a population with its cattle in villages. This possibly refers to the settlement of the prisoners of war among which were the above-mentioned children.23 A more securely-dated example of men and women (total: 544), seemingly presented as spoils of war during the reign of Taharqa, and enumerated according to ethnonyms or toponyms, can be found in his long inscription from Sanam.24

On the Enthronement stela of Anlamani (late 7th century BCE) from Kawa (Kawa VIII, lines 19-20, Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Æ.I.N. 1709), it is stated that his soldiers gained control of all the women, children, small cattle and property in the land Bulahau (b-w-r3-h-3-y-w) and that the king appointed the captives as male and female servants of the gods.25 This indicates that Anlamani, like Taharqa, appointed at least some prisoners of war to the temples.26

In the Annals of Harsiyotef (Cairo JE 48864, lines 68-70) from his 35th regnal year in the early 4th century BCE, the king states that he gave booty (ḥ3ḳ) to Amun of Napata, 50 men, 50 women, together making 100.27 The text (line 87-88) further states that the king took, among others, male and female servants in the land of Metete.28 Likewise, in the Annals of Nastasen (Stela Berlin ÄMP 2268, lines 44-46), from his 8th regnal year in the last third of the 4th century BCE, the king states that he gave a total of 110 men and women to Amun of Napata.29 As noted by Jeremy Pope, there is no reason to impose here an artificial distinction between a donation text and a record of war.30 In fact, there is also no such division in ancient Egyptian records of war and the Kushite records of war bear many similarities to those of ancient Egypt, especially when lists of spoils of war are concerned. Nastasen also claims (lines 46-49) that he captured Ayonku, the ruler connected to the rebels and that he took all the women, all the cattle, and much gold. The list mentions 2,236 women.31 Compared to the number of men and women given to the temple of Amun at Napata, this is a significantly larger number, which indicates that a majority of the prisoners actually did not end up as property of the temple. We can only speculate that they were distributed elsewhere, possibly even among the soldiers.32 Nastasen also seized the ruler Luboden and all the women in his possession (line 51).33 He also seized Abso, the ruler of Mahae, and all their women (line 53).34 Nastasen went against the rebellious land of Makhsherkharta and seized the ruler, as well as all of that by which the ruler sustained people, and all the women (line 55).35 Finally, Nastasen seized Tamakheyta, the ruler of the rebellious land Sarasarat, and caused the plundering of all their women (line 58).36

Common to all these Napatan and Meroitic texts written in Egyptian is the order in which different prisoners of war are listed, which is always the same. The enemy ruler is listed first, followed by the enemy men, women and children. No difference is made between male and female children. This demonstrates an intersectional hierarchy based on status, gender, and age. The enemy ruler was the most valued, then came enemy men, women and children, in that same order. An interesting question is if this intersectional hierarchy mirrors that of ancient Sudanese society or if it was only imposed on its enemies. That male and female prisoners of war feature together with children, including even those of foreign rulers donated to temples, comes as no surprise. The individual temples of Amun in Kush also functioned as centres of territorial government and redistribution.37 Some lines in the Annals of Nastasen refer to imprisoned women in a rhetorical manner, stating rather generally that all women of the enemy were taken, instead of providing a number like in earlier sources.

Currently, the textual evidence written in Merotic script is very scarce, and our understanding of the language is not on a level which allows for a detailed reading for most preserved texts. Nevertheless, several experts in Meroitic language and script have recognized the mentioning of prisoners of war in the Hamadab Stela of Amanirenas and Akinidad (British Museum 1650) from the late 1st century BCE.38 According to the new reading of Claude Rilly, the second (small) Hamadab stela (REM 1039) mentions Akinidad and the sites where the Roman prefect Petronius fought against the Meroites, namely Aswan (Meroitic “Sewane”), Qasr Ibrim (Meroitic “Pedeme”), and Napata (Meroitic “Npte”). According to Rilly, the stela also mentions the beginning of the war in its 3rd and 4th lines: “the Tmey have enslaved all the men, all the women, all the girls and all the boys”.39 Interestingly, if Rilly´s reading is correct, this would mean that when Meroitic folk were taken as prisoners by enemies, a gender differentiation was made among children and/or adolescents. The following discussion will focus on the possible iconographic evidence of the conflict between Meroe and Rome.

2.2. Iconographic Evidence¶

Unlike in ancient Egypt, ancient Nubian iconographic evidence for the taking of prisoners of war is rather scarce when the bound prisoner motif is excluded from the corpus. Even less attested are depictions of women and children being imprisoned.

One rare instance of such a depiction is found in temple M250, located about 1km to the east-southeast of the centre of the city of Meroe. John Garstang first investigated the temple in 1910-1911 together with Archibald H. Sayce. The temple M250 was investigated further by Friedrich Hinkel from 1984 to 1985. He dated it to the late 1st century BCE and early 1st century CE because of the royal cartouches of Akinidad found on fallen blocks of the cella’s north wall.40 The earliest temple on the site, which is northwest of M250, had probably already been built in Aspelta’s reign (the beginning of the 6th century BCE) in the form of a cella on top of a podium.41 According to László Török, the temple was dedicated in its later form to the cult of Re or, more precisely, to the unification of Amun with Re.42 Hinkel interpreted it more carefully as a temple of Amun.43

So far, the battle reliefs of M250 were analyzed by several authors. It is Hinkel who published the temple and gave the most detailed description and analysis of the relief blocks to date.44 According to Török, the decoration of the façades had a “historically” formulated triumphal aspect.45 Before the publication of the temple by Hinkel, Steffen Wenig assigned them to the reign of Aspelta because his stela was found on the site. Wenig related the reliefs to the ones from the B500 temple of Amun at Gebel Barkal, not knowing at that time that they predate M250.46 Inge Hofmann analyzed the war reliefs in detail regarding the weapons and equipment worn by the Meroites and emphasized that the weapons they use are post-Napatan. Based on the kilts and hair feathers worn by some of the enemies of Meroites in these scenes, she concluded that they are southerners, but that they cannot be associated with any specific Sudanese community.47 This type of enemy wearing a kilt and feathers is also found as a bound prisoner on the pylon of the tomb chapel of Begrawiya North 6 (the tomb of Amanishakheto).48 It is also depicted on the east wall painting from the small temple M292, better known because of the head of a statue of Augustus, which was buried in front of its entrance.49 According to Florian Wöß, this type of enemy can be classified as an Inner African Type. It is most numerous among Meroitic depictions of enemies and Wöß argues that it could have therefore represented a real threat to the Meroites.50 This conclusion resonates well with the interpretation of the Meroitic kingdom as having a heartland in the Nile Valley, at Keraba, and perhaps also the southland. The Meroitic kingdom was surrounded by various neighbouring communities that could have posed a real threat and were only occasionally under Kushite control.51 As we have already seen, numerous texts refer to conflicts with these communities outside the realm of the Kushite kingdom.

Hinkel has already concluded that the north wall of M250 depicts women and children taken by the Meroites in their raid of the First Cataract, as reported by Strabo in Geography (17. I. 54),52 and that the south wall depicts a conflict with some population that the Meroites encountered in Lower Nubia.53 However, if Meroe is understood as the centre of the axis, then the enemies depicted on the southern wall are unlikely to depict Lower Nubians. We know that during the last decades of the 1st century BCE Lower Nubia was not hostile to Meroe, but on the contrary, that it rebelled against Rome. Gaius Cornelius Gallus reports in his trilingual stela from Philae, erected in 29 BCE, that he placed a local tyrant to govern Triakontaschoinos (Lower Nubia), which became part of the province of Egypt and established a personal patron/client relationship with the king of Meroe.54 This arrangement obliged inhabitants of Triakontaschoinos to pay taxes.55 Roman emperor Augustus then ordered Lucius Aelius Gallus, the second prefect of Egypt, to prepare a military expedition against province Arabia Felix. Aelius Gallus regrouped the forces stationed in Egypt and took c. 8000 of the 16800 men in three legions and 5500 of the auxiliary forces. The expedition was carried out in 26-25 BCE and ended with Roman defeat. The inhabitants of Triakontaschoinos received the news of Aelius Gallus’ failure in Arabia and revolted in the summer of 25 BCE. The aim of the revolt was to end the previously established status of Triakontaschoinos and the obligation of paying tax to Rome. Concurrent with this revolt, there were local rebellions against the pressure of taxation in Upper Egypt.56 The rebels might also have received help from the king of Meroe. Meroe probably tried to use the opportunity presented by the revolt in Triakontaschoinos and Upper Egypt to establish the northern frontier in the region of the First Cataract.57 Therefore, it is unlikely that the southern enemy depicted on the walls of temple M250 represents Lower Nubians. They were not hostile toward Meroe at the time before the building of the temple M250 under Akinidad. On the contrary, they were its allies in war with Rome.

Regarding the representations of women and children as prisoners of war in temple M250, Török found parallels in New Kingdom Egyptian (ca. 1550-1070 BCE) reliefs,58 whereas Hinkel found parallels both in New Kingdom Egyptian and Neo-Assyrian reliefs (ca. 911-609 BCE).59 One must, however, stress that in the case of the New Kingdom Egyptian reliefs, the parallels are both thematic and iconographic, whereas in the case of Neo-Assyrian reliefs, the parallels are strictly general and thematic (e.g. imprisonment). In this paper, I will focus more closely on the thematic and iconographic parallels from New Kingdom Egypt and Nubia, considering the fact that general thematic parallels (e.g. imprisonment) are found in many cultures and are not particularly helpful in better understanding the decorative program of M250.

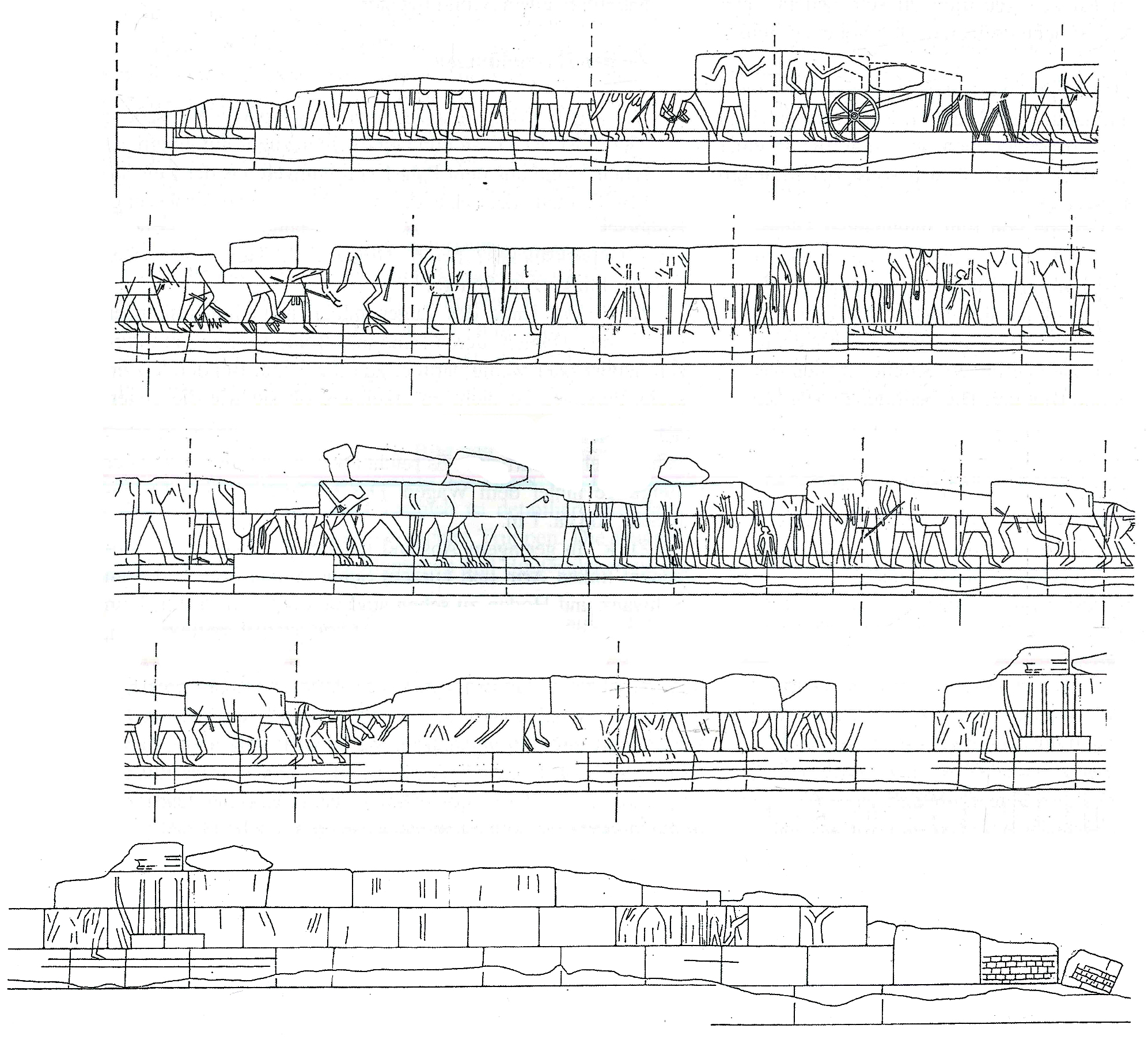

Women and children are found both on the south and the north wall of the temple M250. The blocks with representations of women and children are part of the preserved in situ lowest register of the north wall. Its preserved height is ca. 110cm above the crepidoma.60 Its register depicts an east-west oriented procession of armed men, horse riders, and chariots who join a battle. After the battle scene, the same register continues with the procession of armed men, with nude women and children in front of them (Figure 1).

The women and children are preceded by men with oval shields and cattle in front of them, after which comes one more group of nude women and children. They are approached by oppositely-oriented men, probably in a battle. After them, the register continues in an east-west orientation towards a columned building, which is presumably a representation of a temple.61 The register continues behind this columned building and there is a break here, after which comes poorly preserved representations of round huts and trees.62 Only the lower parts of the figures of women and children are preserved on the north wall, so it is hard to say more about them. However, the women and children seem to be nude. The gender of the children cannot be identified because the representations were later damaged in the genital area. There are two groups and in between them there are cattle. The groups are flanked with men who lead them forward.

Figure 1. Relief blocks from the north wall of M250 in the sequence east-west (redrawn after Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1: 140-141, Abb. 39, 40, 41, 42).

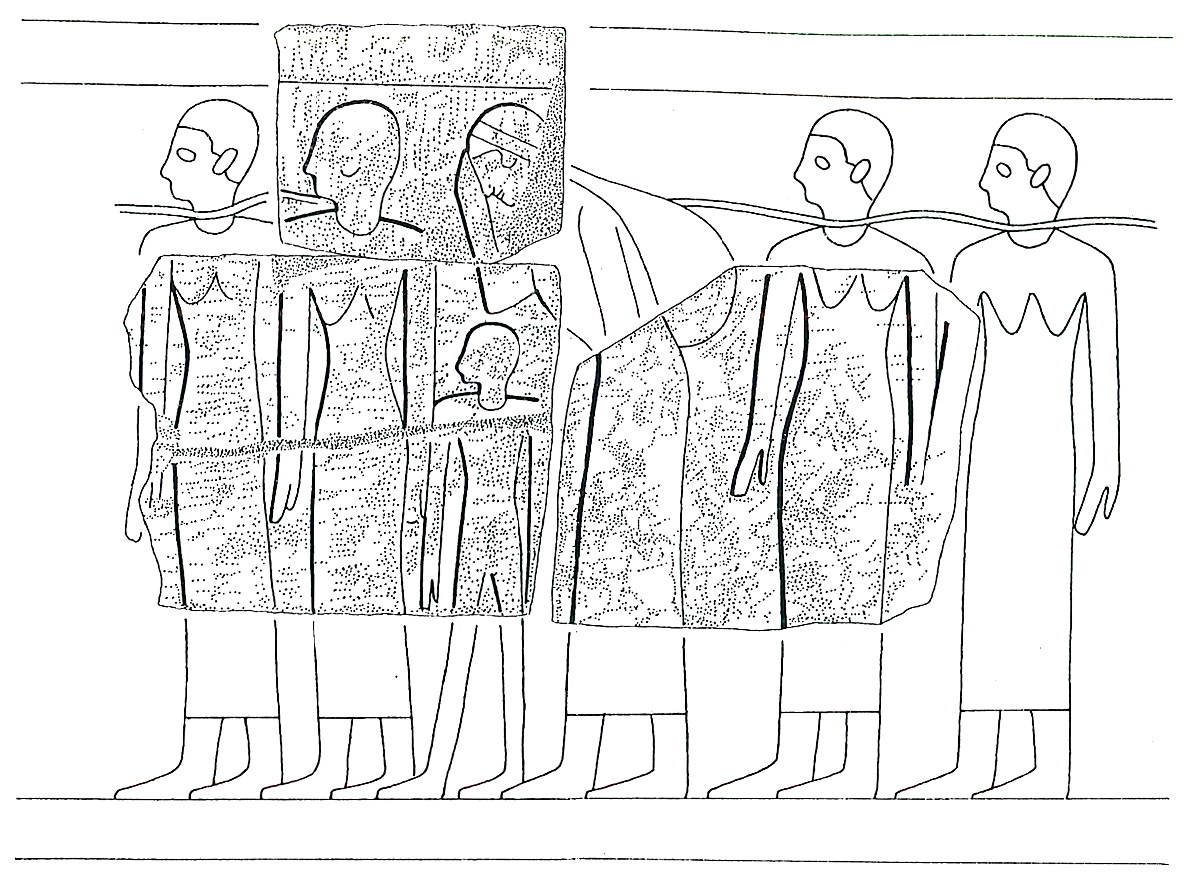

The blocks of the southern wall, with representations of women and children, are not found in situ, but rather in the vicinity of the south wall. Some of them can be joined and some of these joints present evidence for at least two registers. In one case, the upper register of the two depicts both women and children as prisoners of war, while the lower register depicts ship-fragments 198, 322, 323, 319, and 190.63 The figures in the two registers are differently oriented. Additionally, one more boat representation with a head of a ram possibly indicates a relation to Amun (fragments 113 and 106).64 It is oriented in the same direction as the previous boat. On the blocks of the south wall, both men and women are depicted as prisoners of war next to children (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Relief blocks (fragments 943+185+180 and 222) of the south wall of M250 with fragmented depictions of imprisoned women and children, line drawing (redrawn after Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 2b: C11).

Unlike the women from the north wall, the women from the south wall are half-dressed. The breasts depicted on some of them (fragments 188, 214, 136, 943, 185, 222, 199, 847, 849, 811) indicate their sex, while the sex of some of the children figures is depicted via smaller breasts (fragment 236). Some of the women from the south wall are carrying baskets with children on their backs, held with the help of a tumpline (fragment 943, 849). In New Kingdom Egyptian iconography, this is a characteristic of Nubian women when depicted with children in tribute scenes.65 Women are depicted with children either next to them, held in their arms, raised high in the air (fragments 210, 849), or in between them (fragments 185, 189, 230, 175). Both men and women on the south wall have ropes tied around their necks, with several people in a row being tied on the same rope (fragments 136, 943, 189, 34, 102, 39, 408, 847, 844, 849, 811).

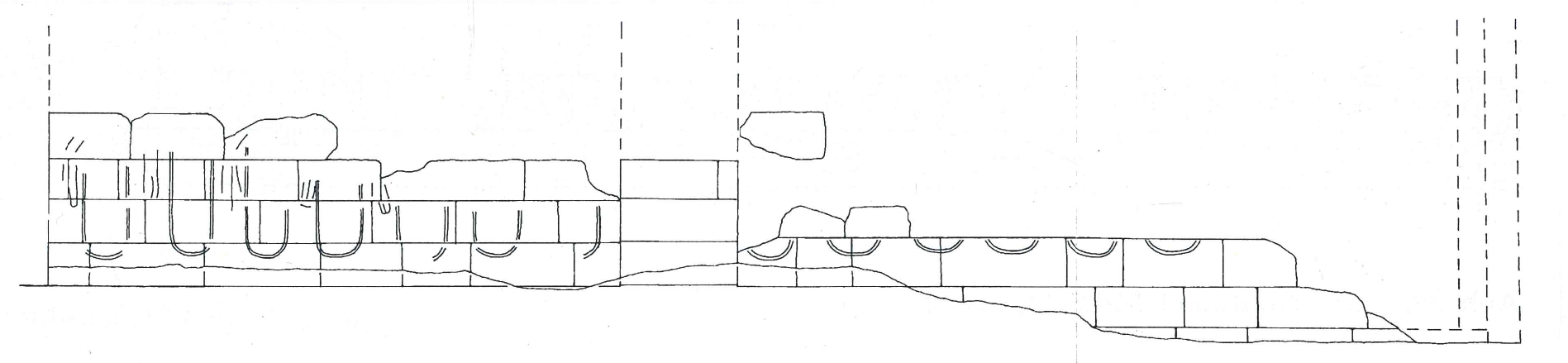

Figure 3. Empty oval name rings on the northern part of the pylon of M250 (redrawn after Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1: 139; Abb. 37b).

Hinkel related the construction of the M250 temple to the treaty that the Meroites negotiated with Augustus on Samos in 21/20 BCE. He relates the taking of women and children as prisoners on the north wall to the sacking of Philae, Elephantine, and Syene by the Meroites,66 as reported by Strabo in Geography, 17. I. 54.67 The context of the war reliefs on the northern wall of the temple indeed indicates a northern conflict. It is interesting that the oval name rings for the toponyms or ethnonyms of defeated enemies are left blank on the northern part of the temple pylon (Figure 3),68 and were only filled in with Meroitic hieroglyphs on the southern part of the temple pylon, which have thus far not been identified with certainty.69 In the light of Strabo’s Geography 17. I. 54, in which he writes that when told that they should go to Augustus, the Meroites answered they do not know who that was,70 one has to consider that the Roman dominated world beyond the province of Egypt was unknown or insufficiently known to the Meroites. This explains the empty oval name rings on the northern part of the temple pylon. Except for the generic Arome referring to Rome71 and Tmey referring to the Northeners,72 we do not know of any other Roman toponyms from Meroe so far and it is likely that in the first century BCE and first century CE the Meroites indeed did not know of any others. If the reliefs on the northern walls of the temple depict a Meroitic raid on the First Cataract sites, then we have to take into account that they imprisoned the local population, consisting also of women and children and not only of men. These women and children could also have been local and not necessarily immigrants after the Roman takeover of Egypt. The iconographic evidence from M250 corresponds well with the textual attestations for the taking of prisoners of war of different ages and genders, and allocates them to temples of Amun. Interestingly, just like in ancient Egyptian iconography of the New Kingdom, there is an absence of violence against women and children.73 Bearing in mind the idea that frames of war regulate what is reported and represented in various media, we can consider the possibility that some realities of war such as violence against non-combatants were censured due to socially determined taste. Hurting women and children was probably considered a form of illegitimate violence and although it probably occurred, it was not communicated to local audiences.

3. Feminization of Enemies in Texts¶

The feminization of enemies is a common cross-cultural motif in war discourse, both textual and visual. As anthropologist Marilyn Strathern argued, “relations between political enemies stand for relations between men and women”.74 Numerous examples are known for this from ancient Egypt and Neo-Assyria and these are extensively dealt with elsewhere.75 Here, the focus will be on the feminization of enemies in Kushite war discourse.

One attestation for the feminization of enemies without parallels, to the best of my knowledge, is found on the Triumphal Stela of Piye (Cairo JE 48862, 47086-47089, lines 149-150), the founder of the 25th Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled between 744-714 BCE: “Now these kings and counts of Lower Egypt came to behold His Majesty’s beauty, their legs being the legs of women.” js gr nn <n> nswt ḥ3(tj).wꜥ nw T3-mḥw jj r m33 nfr.w ḥm=f rd.wj=sn m rd.wj ḥm.wt.76 Nicolas-Christophe Grimal has translated this part of the text in a way that suggests that the legs of the kings and counts of Lower Egypt trembled like those of women.77 One has to stress that the adjective tremblant (French for “trembling”) is not written in the text, but is rather assumed by Grimal. On the other hand, Hans Goedicke’s translates rd.wj=sn not as legs, but knees instead.78 According to Robert K. Ritner, this means that they were trembling in fear,79 and similarly, according to Amr el Hawary, this could indicate that enemies of Piye had their legs bent at the knees from fear.80 However, David O’Connor and Stephen Quirke understand the text as a metaphor for the femininity of Piye’s enemies, because the legs of women are smooth-skinned.81 Yet, although both men and women shaved in Egypt and Nubia, we cannot assume that body hair removal was restricted only to women. For Nubia, at least, this is indicated by the description of Kushites in the Bible as tall and smooth-skinned people (Isaiah 18:7).82 Later in the text, it is stated that three of these kings and counts stayed outside the palace “because of their legs” (r rd.wj=sn), and only one entered. El Hawary postulates that this could be related to the previous comparison with the legs of women.83 Another case is possibly alluded to later in the same text when it states “You return having conquered Lower Egypt; making bulls into women” (jw=k jy.tw ḥ3q.n=k T3-mḥw jr=k k3.w m ḥm.wt).84 Bearing in mind that in the Instructions of Ankhsheshonqy (X, 20), an Egyptian text of the Ptolemaic period (305-30 BCE), bulls are contrasted to the vulvas which should receive them,85 we can argue that, in both cases, bulls stand for men, or at least masculinity, in both the human and animal world. It is interesting that on the Triumphal stela of Piye, men from the palace of the Lower Egyptian king Nimlot paid homage to Piye “after the manner of women” (m ḫt ḥm.wt).86 Maybe this indicates that there was also a manner in which men are supposed to pay homage to the king, and that the defeated kings and counts of Lower Egypt failed to do this, or at least the text wants us to believe that. The failed masculinity of Nimlot in the text of the stela was extensively studied most recently by Mattias Karlsson. Next to the motives already mentioned, additional arguments are rich and complex. Piye is representing ideal masculinity, contrasted with failed masculinity of Nimlot. This can be observed both in the text and in the iconography of the stela. For example, Nimlot is holding a sistrum, a musical instrument usually linked to women (e.g. priestesses of Hathor), while he is standing behind his wife and not depicted in the usual front-facing manner. His wife speaks for him and appears as the head of his household.87 To these arguments one can also add the fact that the silhouette of the defeated Egyptian princes in proskynesis differs in shape from usual representations of men. Their bodies seem to be curvier as in Kushite depictions of women. An allusion of sexual domination is not directly communicated, but it might have been implied.

There are other attestations of the feminization of enemies in texts composed for the Kushite kings. In the Annals of Harsiyotef (Cairo JE 48864, line 89) we are informed about his conflicts with the Mededet people in his 6th regnal year. After taking spoils of war, the ruler of Mededet was sent to Harsiyotef, saying: “You are my god. I am your servant. I am a woman. Come to me” (ntk p(3)=j nṯr jnk p(3)=k b3k jnk sḥm.t my j-r=j).88 In this attestation, we have a direct speech of the enemy, who, according to the text, identifies himself with a woman. Of course we are safe to assume that these words were put in his mouth by the composer of the text of the stela. El Hawary has already made a connection between the passage from the Annals of Harsiyotef and this passage from the Triumphal stela of Piye, describing the homage to Piye in a womanly manner. Interestingly, no such attestations, as far as I am aware, are known from Egyptian sources.89

4. Meroitic Non-royal and Royal Women in War¶

In Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE), Agatharchides reports how the Aethiopians employed women in war: “They also arm their women, defining for them a military age. It is customary for most of these women to have a bronze ring through one of their lips”.90 This is repeated by Strabo in first century CE.91

The conflict between Meroe and Rome was mentioned in the discussion of the iconography of temple M250. One interesting aspect of this conflict is the Roman perspective on the rulership of Meroe. Strabo mentions the participation of a Meroitic queen in war against Rome, describing Queen Kandake here as “a manly woman who had lost one of her eyes”.92 We should be careful with crediting such descriptions much value. Not only did Strabo confuse a Meroitic royal title that probably indicated a mother of a king,93 but there is also a tendency among Graeco-Roman authors to depict foreign women as masculine thus creating an inverted image to gender expectations in their own society. Such inversions could have served the purposes of shocking their audience and enhancing the otherness of foreign lands and peoples. This is evidently an example of ideological gender inversion used as a sign of barbarism, especially towards foreign women, in the works of Strabo.94

Still, that the soldiers in the Roman army knew of a woman that was referred to by her subjects simply as kandake is also demonstrated by a ballista ball (British Museum EA 71839) with a carbon-ink inscription KANΔAΞH/Kandaxe from Qasr Ibrim. On the ball, the second and third lines of text can be understood as a personal message for the queen: “Just right for you Kandaxe!”.95 Clearly, it is questionable if the ones who actually found themselves in Nubia during the conflict with Meroe knew the name of the enemy ruler. It is also possible that they knew, but referred to her as everyone else.

5. Meroitic Queens and Enemies: Iconographic Evidence¶

The smiting of an enemy scene originates from ancient Egyptian iconography, with its earliest known evidence found in tomb 100 in Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt, dated to the Naqada IIC period, around 3500 BCE. In Egypt, the motif has remained in the decoration of temple pylons, private and royal stelae, and small finds for more than 3500 years. Its latest known appearance is found on temple reliefs from the Roman period when emperors Domitian, Titus, and Trajan are depicted smiting. Kushite kings are also depicted smiting enemies and the motif was adopted from ancient Egyptian art.96

What differentiates the use of this motif in ancient Nubia during the Meroitic period from its use both in the contemporary Roman province of Egypt and in earlier periods of Nubian history is the fact that certain queens are depicted smiting male enemies in Meroitic iconography. Some ancient Egyptian queens are also depicted smiting enemies. However, these enemies are always female when the figure who is delivering the blow is depicted as a woman.97 This is because a king is never depicted delivering harm to foreign women and children, at least in the New Kingdom. The king always defeats the supposedly stronger enemy.98 Although the inclusion of queen Nefertiti smiting female enemies alongside scenes of Akhenaten smiting male enemies probably indicates the elevation of her status during the period of his rule,99 Nefertiti is nevertheless not the dominant figure in such depictions; the dominant figure remains the smiting king because of the gender of the enemies he smites. Male enemies were considered more dangerous than female. When a female ruler like Hatshepsut (ca. 1479-1458 BCE) of the 18th Dynasty is depicted smiting or trampling male enemies, she herself is depicted as a king –a man– and her identity is indicated by the accompanying text that lists her name and royal titles.100

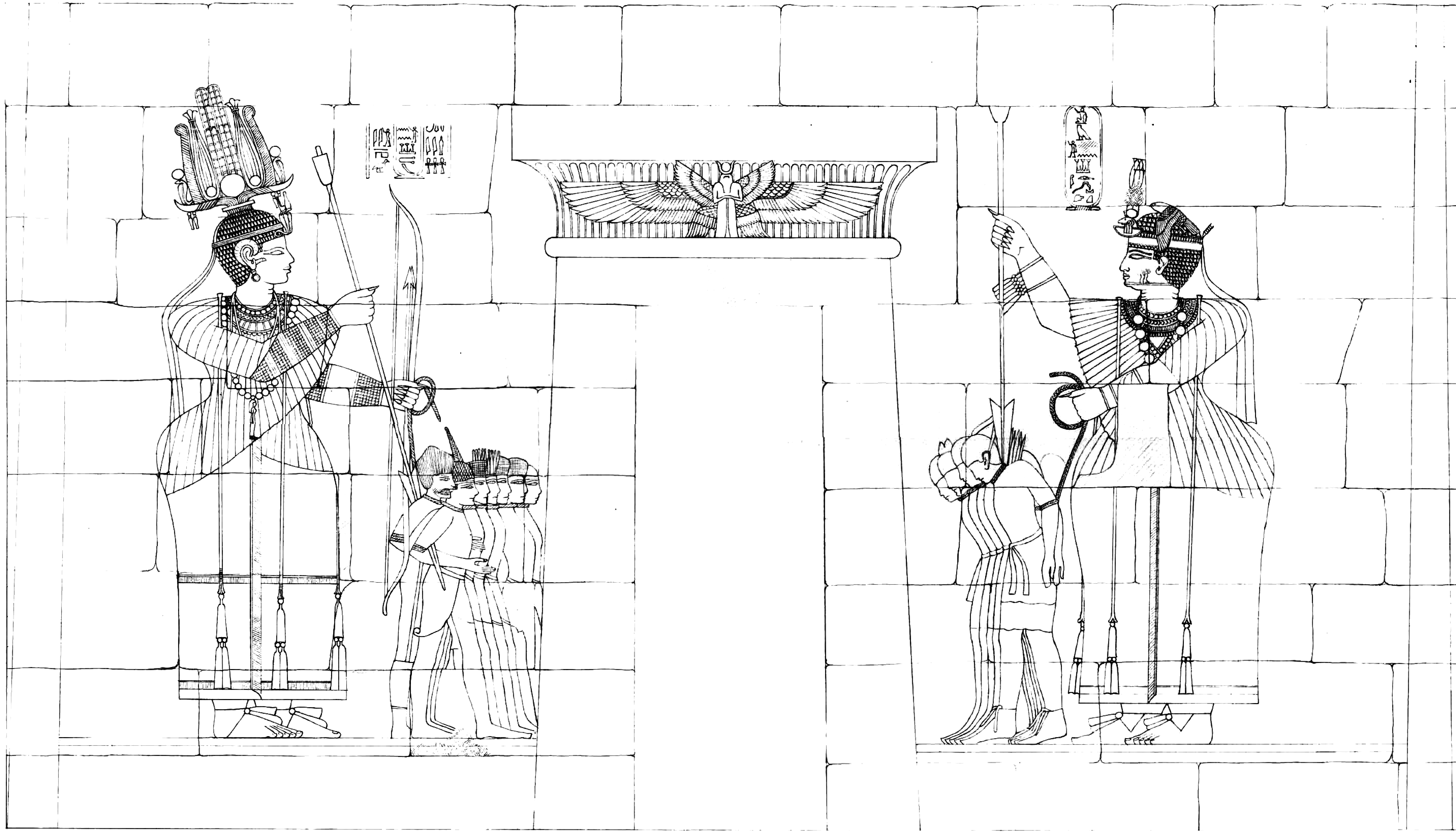

The Meroitic case is interesting precisely because certain royal women can be depicted smiting and spearing male enemies. Amanishakheto (1st century CE) is depicted spearing enemies on the pylon of her pyramid Begrawiya North 6 in Meroe, both to the left and right of the pylon entrance (Figure 4). On the left, she holds a bow, arrow, and rope in her left hand and a spear in her right hand. The rope in her left hand extends to the necks of the enemies to which it is tied. Seven enemies are depicted with rope tied around their necks and with their arms tied behind their backs. On the right, Amanishakheto holds a rope in her left hand which binds four enemies around their necks. Their arms are also bound behind their backs. In her right hand, she holds a spear with which she spears the enemies.101 On her stela from Naqa she is depicted before the enthroned Lion God above a group of bound enemies.102

Figure 4. Amanishakheto spearing enemies, pylon, pyramid Begrawiya North 6, line drawing (Chapman & Dunham. Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal, Pl. 17).

Figure 5. Shanakdakheto (?) sitting on a throne with bound enemies underneath, north wall, pyramid Begrawiya North 11, line drawing (Chapman & Dunham. Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal, Pl. 7A).

Bound enemies are additionally depicted under the throne of the queen on the north wall of pyramid Begrawiya North 11 attributed to Shanakdakheto (Figure 5).103 Nine bows, the traditional symbol for enemies originating from ancient Egypt, are depicted under the throne of Amanitore of the 1st century CE (Figure 6), just as they are depicted under the throne of Natakamani in the pyramid Begrawiya North 1 of queen Amanitore.104

Figure 6. Amanitore sitting on a throne with the nine bows underneath, south wall, pyramid Begrawiya North 1, line drawing (Chapman & Dunham. Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal, Pl. 18B).

Amanitore is depicted smiting enemies on the pylon of the Lion Temple in Naga.105 There, she is paired with Natakamani, who is also depicted smiting enemies (Figure 7). Natalia Pomerantseva interpreted this as “hero worshiping of the woman-image”, adding that “it is impossible to imagine the frail Egyptian woman’s figure in the part of chastisement of enemies”.106 Yet, as we have seen, some Egyptian royal women are depicted in violent acts such as the smiting and trampling of female enemies and the reason they are not depicted doing the same to male enemies is status-related. If they would be depicted as women smiting or trampling male enemies, this would elevate their status to the one of kings; clearly, attention was paid to avoid this. In the case of the Meroitic queens, the gender of the enemy was not an issue. Jacke Phillips has also emphasized that the smiting of enemies by Merotic queens is among the corpus of scenes, which were formerly restricted to kings, but Phillips did not take the argument further. The reason for the creation of these scenes can be seen in the specific status of royal women in Meroitic ideology.107 However, we also have to bear in mind that, considering the number of known Napatan and Meroitic royal women, the smiting scenes of Amanishakheto and Amanitore in the 1st century CE are an exception rather than rule. Interestingly, the smiting and trampling scenes of Tiye and Nefertiti are also an exception rather than the rule, and this exception in ancient Egyptian iconography has so far been explained as a consequence of the increasing importance of royal women both in politics and religion.108 We can certainly say Amanishakheto and Amanitore also lived in exceptional times, during and after the conflict of Meroe with Rome. It is possible that in these times certain exceptional women rose to unparalleled positions.109

Figure 7. Natakamani and Amanitore smiting enemies, pylon of the temple of Naqa, line drawing (Lepsius, Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien 10, B1. 56).

6. Conclusion¶

Gender as a frame of war has structured both Napatan and Meroitic texts, from lists enumerating the spoils of war to texts dealing with military campaigns. In the first case, this is observable in the order that different categories of prisoners of war are listed, namely enemy rulers (men), then enemy men, women, and children. This same structure for prisoners of wars is found with only slight differences in ancient Egyptian spoils of war examples,110 which can hardly be taken as a coincidence. Since the earlier Napatan texts were written in Egyptian, their structure, at least when lists of spoils of war are concerned, could have been based on an Egyptian pattern. This, then, continued into the Meroitic period. In the second case, namely the texts dealing with military campaigns, how gender as a frame of war operates can be observed in the discursive feminization of enemies in Napatan texts. Just like in ancient Egyptian and Neo-Assyrian texts,111 enemies are discursively framed as women or effemininate. This is in fact a metaphor found in many cultures in which strength is associated with men and weakness is associated with women. Rather than just framing the power relations between the Kushite kings and their enemies, such metaphors strengthen the gender structure of the society itself, privileging men and masculinity. By discursively taking away masculinity from the enemy, these texts are framing them as subordinate and thus legitimizing the subordination of women to men. Unfortunately, the present state of knowledge of the Meroitic language does not allow us to investigate possible feminizations of enemies in the Hamadab stelae written in Meroitic. It would indeed be interesting to know if the same metaphors are used.

The reports of Graeco-Roman writers such as Agatharchides in Diodorus Siculus and Strabo could have been a misunderstanding of Meroitic royal ideology and the figure of kandake. We should, however, not entirely exclude the possibility that women could have participated in war, although we do not have any explicit ancient Nubian textual attestations for this. We also do not have any burials attributed to “warrior women” or “warrior queens”, based on the placement of weapons as grave goods in graves of women.112 Even if such burials were to be found, one would have to be cautious in assigning military activity to women (or men) simply because of the associated weapons. Muscular stress markers or potential traces of trauma on the skeletons would be more indicative, however both could also be found in burials without such associated weapons. Nevertheless, one should not exclude the possibility that Meroitic queens made military decisions, just like, for example, the 17th Dynasty queen Ahhotep or the 18th Dynasty female pharaoh Hatshepsut in Egypt,113 though they probably did not fight in war. The depictions of Meroitic queens smiting enemies should be seen in the context of royal ideology. Unlike Egyptian queens, who are depicted as women smiting enemies only when these enemies are also women, both Meroitic kings and certain Meroitic queens are shown smiting and spearing enemy men. There is no difference in the gender of the enemy and therefore no hierarchy. This can be explained with an elevated status of queenship in Kush, in comparison to ancient Egypt. Unlike in Egypt, where a ruling woman like Hatshepsut had to be depicted as a man when smiting enemies, a ruling woman in Meroe could be depicted as a woman smiting male enemies.

Clearly, gender was one of the frames of war in ancient Nubia, with a tradition spanning several centuries and possibly even having ancient Egyptian roots, at least where the structure for listings of the spoils of war and some metaphors for enemies are concerned. However, as I have shown, there are certain expressions without parallels in ancient Egyptian texts, which testify to an independent, but equally male-privileging discourse. Gender as a frame of war (sensu Judith Butler) justified state violence against enemies by discursively representing them as women. In this manner, asymmetrical power relations in one domain (war) were tied to asymmetrical power relations in another domain (gender). This is a prime example of symbolic violence (sensu Pierre Bourdieu and Slavoj Žižek). Gender relations which place Kushite and enemy women as subordinate to Kushite men are naturalized through a reference to a subordination of enemy men to Kushite men. Simultaneously, the lack of explicit violence conducted against enemy women and children was in a way “the cosmetic treatment of war”, to use the words of Jean Baudrillard. The frame of war such as this one clearly influenced how war and violence is represented and consequently experienced by local audiences who did not participate in war. Some forms of violence are communicated to local audiences in specific manners relying on asymmetrical power relations of gender. Other forms of violence which probably occurred, such as violence against non-combatants, are carefully avoided in texts and images as it was probably hard to justify them.

7. Acknowledgments¶

I would like to express my enormous gratitude to Jacqueline M. Huwyler, M.A. (University of Basel) for proofreading the English of my paper. I am also grateful to Angelika Lohwasser and Henriette Hafsaas for their help in acquiring some of the references.

8. Bibliography¶

Breyer, Francis. Einführung in die Meroitistik. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie 8. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2014.

Burstein, Stanley. “The Nubian Slave Trade in Antiquity: A Suggestion.” In Graeco-Africana: Studies in the History of Greek Relations with Egypt and Nubia. New Rochelle, NY, Athens & Moscow: Aristide D. Caratzas, 1995: pp. 195-205

Butler, Judith. Frames of War. When is Life Grievable? London and New York: Routledge, 2009.

Butler, Judith. The Force of Non-Violence. An Ethico-Political Bind. London and New York: Routledge, 2020.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Masculine Domination, trans. by Richard Nice. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001.

Bourdieu, Pierre. “Symbolic Violence.” In Violence in War and Peace. An Anthology, edited by Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Philippe Bourgois, pp. 339-42. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

Chapman, Suzanne E., and Dows Dunham. Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal. The Royal Cemeteries of Kush III. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1952.

Conkey, Margaret W., and Janet D. Spector. “Archaeology and the Study of Gender.” Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 7 (1984): pp. 1-38.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1.8 (1989): pp. 139-67.

Danielsson, Ing-Marie Back, and Susan Thedéen (eds). To Tender Gender. The Pasts and Futures of Gender Research in Archaeology. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 58. Stockholm: Stockholm University, 2012.

Díaz-Andreu, Margarita. “Gender identity.” In The Archaeology of Identity. Approaches to Gender, Age, Status, Ethnicity and Religion, edited by Margarita Díaz-Andreu, Sam Lucy, Staša Babić, and David Edwards, pp. 1-42. London and New York: Routledge, 2005.

Dieleman, Jacco. “Fear of Women? Representations of Women in Demotic Wisdom Texts.” Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 25 (1998): pp. 7-46.

Dowson, Thomas A. “Why Queer Archaeology? An Introduction.” World Archaeology 32.2 (2000): pp. 161-5.

Eide, Tormod, Tomas Hägg, Richard Holton Pierce, and László Török (eds). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD, vols. I-IV (abbr. FHN). Bergen: University of Bergen, 1994-2000.

Gamer-Wallert, Ingrid. Der Löwentempel von Naqa in der Butana (Sudan) III. Die Wandreliefs. 2. Tafeln. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1983.

Gilchrist, Roberta. Gender and Archaeology: Contesting the Past. London and New York: Routledge, 1999.

Grimal, Nicolas-Christophe. La stèle triomphale de Pi(cankh)y au Musée du Caire. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1981.

Goedicke, Hans. Pi(ankhy) in Egypt. A Study of the Pi(ankhy) Stela. Baltimore: Halgo, Inc., 1998.

Goldstein, Joshua S. War and Gender: How Gender Shapes the War System and Vice Versa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Haaland, Randi. “Emergence of Sedentism: New Ways of Living, New Ways of Symbolizing.” Antiquity 71 (1997): pp. 374-85.

Haaland, Gunnar, and Randi Haaland. “Who Speaks the Goddess’s Language? Imagination and Method in Archaeological Research.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 28.2 (1995): pp. 105-21.

Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette. “Edges of Bronze and Expressions of Masculinity: The Emergence of a Warrior Class at Kerma in Sudan” Antiquity 87 (2013): pp. 79-91.

Hall, Emma Swan. The Pharaoh Smites His Enemy. Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1986.

El Hawary, Amr. Wortschöpfung: Die Memphitische Theologie und die Siegesstele des Pije-zwei Zeugen kultureller Repäsentation in der 25. Dynastie. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 243. Fribourg and Göttingen: Academic Press Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010.

Hinkel, Friedrich W. Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. Forschungs-Archiv F. W. Hinkel. The Archaeological Map of the Sudan Supplement I. 1. Berlin: Selbstverlag des Hrsg., 2001.

Hinkel, Friedrich W. Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. Forschungs-Archiv F. W. Hinkel. The Archaeological Map of the Sudan Supplement I. 2b. Tafelteil C-G. Berlin: Selbstverlag des Hrsg., 2001.

Hofmann, Inge. “Notizen zu den Kampfszenen am sogenannten Sonnentempel von Meroe.” Anthropos 70. ¾ (1975): pp. 513-36.

Jameson, Shelagh. “Chronology of the Campaigns of Aelius Gallus and C. Petronius.” The Journal of Roman Studies 58, 1 & 2 (1968): pp. 71-84

Jensen, Bo, and Matić, Uroš. “Introduction: Why Do We Need Archaeologies of Gender and Violence, and Why Now?” In Archaeologies of Gender and Violence, edited by Uroš Matić and Bo Jensen, pp. 1-23. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2017.

Jones, Horace L. Strabo. The Geography Vol. VIII. Loeb Classical Library 267. London: Harvard University Press, 1957.

Karlsson, Mattias. “Gender and Kushite State Ideology: The Failed Masculinity of Nimlot, Ruler of Hermopolis.” Der Antike Sudan. Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gessellschaft zu Berlin 31 (2020): pp. 99-108.

Kormysheva, Eleonora Y. “Political Relations between the Roman Empire.” In Studia Meroitica 10: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference for Meroitic Studies, edited by Sergio Donadoni and Steffen Wenig, pp. 49-215. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1989.

Kuhrt, Amelie. “Women and War.” NIN: Journal of Gender Studies in Antiquity 2 (2001): pp. 1-25.

Lavik, Marta Høyland. A People Tall and Smooth-Skinned. The Rhetoric of Isaiah 18. Vetus Testamentum, Supplements 112. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

Lepsius, Karl R. Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien. Taffelband 10: Aethiopien, hrsg. von Eduard Naville, bearbeitet von Walter Wreszinski, Leipzig 1913. Nachdruck. Osnabrück: Verlagsgruppe Zeller, 1970.

Lohwasser, Angelika. “Gibt es mehr als zwei Geschlechter? Zum Verhältnis von Gender und Alter.” Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie 2 (2000): pp. 33-41.

Lohwasser, Angelika. Die königlichen Frauen im antiken Reich von Kusch: 25. Dynastie bis zur Zeit des Nastasen. Meroitica 19. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2001.

Lohwasser, Angelika. “Queenship in Kush: Status, Role and Ideology of Royal Women.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 38 (2001): pp. 61-76.

Lohwasser, Angelika. “Kush and Her Neighbours beyond the Nile Valley.” In The Fourth Cataract and Beyond. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies. British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 1, edited by Julie R. Anderson and Derek A. Welsby, pp. 125-34. Leuven: Peeters, 2014.

Lohwasser, Angelika. “The Role and Status of Royal Women in Kush.” In The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World, edited by Elizabeth D. Carney and Sabine Müller, pp. 61-72. London and New York: Routledge, 2020.

Lohwasser, Angelika, and Jacke Philipps. “Women in Ancient Kush.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by Geoff Emberling and Bruce Williams, pp. 1015-32. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Macadam, Miles Frederick Laming. The Temples of Kawa. I. The Inscriptions. Text. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949.

Macadam, Miles Frederick Laming. The Temples of Kawa. I. The Inscriptions. Plates. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949.

Matić, Uroš. “Der Kopf einer Augustus-Statue aus Meroe”. Sokar 28 (2014): pp. 68-71.

Matić, Uroš. “Die ''römische'' Feinde in der meroitischen Kunst.” Der Antike Sudan. Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin 26 (2015): pp. 251-62.

Matić, Uroš. “Children on the Move: ms.w wr.w in the New Kingdom Procession Scenes.” In There and Back Again – the Crossroads II Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Prague, September 15-18, 2014, edited by Jana Mynářová, Pavel Onderka, and Peter Pavúk, pp. 373-90. Prague: Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts, 2015.

Matić, Uroš. “The Best of the Booty of His Majesty: Evidence for Foreign Child Labor in New Kingdom Egypt.” In Global Egyptology. Negotiations in the Production of Knowledges on Ancient Egypt in Global Contexts, edited by Christian Langer, pp. 53-63. London: Golden House Publications, 2017.

Matić, Uroš. “Her Striking but Cold Beauty: Gender and Violence in Depictions of Queen Nefertiti Smiting the Enemies.” In Archaeologies of Gender and Violence, edited by Uroš Matić and Bo Jensen, pp. 103-21. Oxford: Oxbow Books 2017.

Matić, Uroš. Body and Frames of War in New Kingdom Egypt: Violent treatment of enemies and prisoners. Philippika 134. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2019.

Matić, Uroš. “Begehrte Beute. Fremde Frauen als Raubgut im Alten Ägypten.” Antike Welt 4.19 (2019): pp. 15-8.

Matić, Uroš. “Traditionally Unharmed? Women and Children in NK Battle Scenes.” In Tradition and Transformation. Proceedings of the 5th International Congress for Young Egyptologists, Vienna, 15-19 September 2015. Denkschriften der Gesamtakademie 84. Contributions to the Archaeology of Egypt, Nubia and the Levant 6, edited by Andrea Kahlbacher and Elisa Priglinger, pp. 245-60. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2019.

Matić, Uroš. “Pharaonic Plunder Economy. New Kingdom Egyptian Lists of Spoils of War through an Archaeological Perspective.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists 24-30 August 2020. Session: The Archaeology of Recovery. The Aftermath of War.

Matić, Uroš. Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. London and New York: Routledge, 2021.

McCoskey, Denise Eileen. “Gender at the Crossroads of Empire: Locating Women in Strabo’s Geography.” In Strabo’s Cultural Geography: The Making of a Kolossourgia, edited by Daniela Dueck, Hugh Lindsay, and Sarah Pothecary, pp. 56-72. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Minas-Nerpel, Martina, and Stefan Pfeiffer. “Establishing Roman Rule in Egypt: The Trilingual Stela of C. Cornelius Gallus from Philae.” In Tradition and Transformation: Egypt under the Roman Rule. Proceedings of the International Conference, Hildsheim, Roemer- and Pelizaeus-Museum, 3-6 July 2008. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East Vol. 41, edited by Katja Lembke, Martina Minas-Nerpel, and Stefan Pfeiffer, pp. 265-98. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Nordström, Hans-Åke. “Gender and Social Structure in the Nubian A-Group.” In Combining the Past and the Present. Archaeological Perspectives on Society, edited by Terje Oestigaard, Nils Anfinset, and Tore Saetersdal, pp. 127-33. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 2004.

O’Connor, David, and Stephen Quirke. “Introduction: Mapping the Unknown in Ancient Egypt.” In Mysterious Lands. Encounters with Ancient Egypt, edited by David O’Connor and Stephen Quirke, pp. 1-22. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.

Parkinson, Richard B. “‘Homosexual’ Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 81 (1995): pp. 57-76.

Perry, Elizabeth P., and Rosemary A. Joyce. “Providing a Past for Bodies that Matter: Judith Butler's Impact on the Archaeology of Gender.” International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies 6.1 (2001): pp. 63-76.

Peust, Carsten. Das Napatanische. Ein ägyptischer Dialekt aus dem Nubien des späten ersten vorchristlichen Jahrtausends. Texte, Glossar, Grammatik. Monographien zur Ägyptischen Sprache 3. Göttingen: Peust & Gutschmidt Verlag, 1999

Phillips, Jacke. “Women in Ancient Nubia.” In Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World, edited by Stephanie Lynn Budin and Jean MacIntosh Turfa, pp. 280-98. London and New York: Routledge, 2016.

Pomerantseva, Natalia A. “The View on Meroitic Kings and Queens as it is Reflected in Their Iconography.” In Studien zum antiken Sudan. Akten der 7. Internationalen Tagung für meroitistische Forschungen vom 14. bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/bei Berlin. Meroitica 15, edited by Steffen Wenig, pp. 622-32. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1999.

Pope, Jeremy. The Double Kingdom under Taharqo. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 69. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014.

Raue, Dietrich (ed.). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Vols. I and II. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019.

Redford, Donald. “Taharqa in Western Asia and Libya.” Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies 24 (1993): pp. 188-91.

Revez, Jean. “Une stèle inédite de la Troisième Période Intermédiaire à Karnak: une guerre civile en Thébaïde?” Cahiers de Karnak 11 (2003): pp. 535-69.

Rilly, Claude. “New Advances in the Understanding of Royal Meroitic Inscriptions.” In 11th International Conference for Meroitic Studies. Abstract. 2008. www⁄http://www.univie.ac.at/afrikanistik/meroe2008/abstracts/Abstract%20Rilly.pdf

Rilly, Claude. “Meroitische Texte aus Naga.” In Königsstadt Naga. Grabungen in der Wüste des Sudan, edited by Karla Kröper, Sylvia Schoske, and Dietrich Wildung, pp. 176-201. München-Berlin: Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, 2011.

Rilly, Claude. “Fragments of the Meroitic Report of the War Between Rome and Meroe.” 13th Conference for Nubian Studies, September 2014, Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Abstract. 2014

Rilly, Claude and De Voogt, Alex. The Meroitic Language and Writing System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Ritner, Robert Kriech. The Libyan Anarchy. Inscriptions from Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period. Sociey of Biblical Literature 21. Atlanta: Society for Biblical Literature, 2009.

Shinnie, Peter L., and Bradley, Rebecca J. “The Murals from the Augustus Temple, Meroe.” In Studies in Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Sudan; Essays in Honor of Dows Dunham on the Occasion of His 90th Birthday, June 1, 1980, edited by William Kelly Simpson, pp. 167-72. Boston: Department of Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art, Museum of Fine Arts, 1981.

Sørensen, Marie Louise Stig. Gender Archaeology. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000.

Spalinger, Anthony J. “Notes on the Military in Egypt during the XXVth Dynasty.” Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 11 (1981): pp. 37-58.

Spalinger, Anthony J. The Persistence of Memory in Kush. Pianchy and His Temple. Prague: Faculty of Arts, Charles University, 2019.

Spalinger, Anthony J. Leadership under Fire: The Pressures of Warfare in Ancient Egypt. Four leçons at the Collège de France. Paris, June 2019. Paris: Soleb, 2020.

Strathern, Marylin. Before and After Gender. Sexual Mythologies of Everyday Life. Chicago: HAU Books, 2016.

Taterka, Filip. “Military Expeditions of King Hatshepsut.” In Current Research in Egyptology 2016. Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Symposium. Jagiellonian University, Krakow 2016, edited by Julia M. Chyla, Joanna Dębowska-Ludwin, Karolina Rosińska-Balik, and Carl Walsh, pp. 90-106. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2017.

Török, László. Meroe City, an Ancient African Capital: John Garstang's Excavations in the Sudan. London: Egypt Exploration Society, 1997.

Török, László. The Kingdom of Kush. Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Handbook of Oriental Studies 31. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 1997.

Török, László. The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art. The Construction of the Kushite Mind, 800 BC-300 AD. Probleme der Ägyptologie 18. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2002.

Török, László. “Sacred Landscape, Historical Identity and Memory: Aspects of Napatan and Meroitic Urban Architecture.” In Nubian Studies 1998. Proceedings of the Ninth Conference of the International Society of Nubian Studies. August 21-26, 1998, Boston, Massachusetts, edited by T. Kendall, pp. 14-23. Boston: Department of African-American Studies Northeastern University, 2004.

Török, László. Between the Two Worlds: The Frontier Region between Ancient Nubia and Egypt 3700 BC-500 AD. Probleme der Ägyptologie 29. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2009.

Williamson, Jacquelyn. “Alone before the God: Gender, Status, and Nefertiti’s Image.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 51 (2015): pp. 179-92.

Wilkins, Alan, Hans Barnard, and Pamela J. Rose. “Roman Artillery Balls from Qasr Ibrim, Egypt.” Sudan and Nubia 10 (2006): pp. 64-78.

Wenig, Steffen (ed.). Africa in Antiquity. The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan. I. The Essays. II. The Catalogue. New York: Brooklyn Museum, 1978.

Wöß, Florian. “The Representations of Captives and Enemies in Meroitic Art.” In The Kushite World. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference for Meroitic Studies, Vienna, 1-4 September 2008. Beiträge zur Sudanforschung 8, edited by Michael H. Zach, pp. 585-600. Vienna: Verein der Förderer der Sudanforschung, 2015.

Zach, Michael H. “A Remark on the ‘Akinidad’ Stela REM 1003 (British Museum EA 1650).” Sudan and Nubia 21 (2007): pp. 148-50.

Žižek, Slavoj. Violence. Six Sideways Reflections. New York: Picador, 2008.

-

For criticism of androcentrism, see Conkey & Spector, “Archaeology and the Study of Gender,” pp. 5-14; for criticism of heteronormative interpretations of the past, see Dowson, “Why Queer Archaeology? An Introduction,” pp. 161-65; for giving voices to ancient women and recognizing different genders behind the archaeological record, see Gilchrist, Gender and Archaeology; Sørensen, Gender Archaeology; Díaz-Andreu, “Gender identity,” pp. 1-42; for viewing gender as a system, see Conkey & Spector, “Archaeology and the Study of Gender,” pp. 4-16; for gender as a result of performative practice, see Perry & Joyce, “Providing a Past for Bodies that Matter: Judith Butler's Impact on the Archaeology of Gender.” The literature in gender archaeology is vast and these are only some frequently quoted studies. ↩︎

-

Haaland and Haaland, “Who Speaks the Goddess’s Language?”; Haaland, “Emergence of Sedentism”; Nordström, “Gender and Social Structure in the Nubian A-Group.” ↩︎

-

Lohwasser, Die königlichen Frauen; Lohwasser, “Queenship in Kush: Status, Role and Ideology of Royal Women,” pp. 61-76; Lohwasser. “The Role and Status of Royal Women in Kush,” pp. 61-72. ↩︎

-

Lohwasser, “Gibt es mehr als zwei Geschlechter? Zum Verhältnis von Gender und Alter,” pp. 33-41. ↩︎

-

Phillips, “Women in Ancient Nubia,” pp. 280-98. The necessity of studying gender, rather than focusing solely on women has also been emphasized recently, Lohwasser and Philipps, “Women in Ancient Kush,” pp. 1015-32. ↩︎

-

Hafsaas-Tsakos, “Edges of Bronze and Expressions of Masculinity”; Karlsson, “Gender and Kushite State Ideology.” ↩︎

-

The contributions in the volume are entirely devoid of gender perspectives, Raue, Handbook of Ancient Nubia. For example, the new Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia has an entry on women in ancient Kush and on the body, but no entry on gender. Other contributions are entirely devoid of gender perspectives. ↩︎

-

Among these, are the questions of ability and disability, gender and intersectionality, and masculinity. Danielsson & Thedéen, To Tender Gender. ↩︎

-

Jensen and Matić, “Introduction: Why do we need archaeologies of gender and violence, and why now?,” pp. 1-23. ↩︎

-

Bourdieu, Masculine Domination, pp. 1-2; Bourdieu, “Symbolic Violence,” pp. 339-42; Žižek, Violence. Six Sideways Reflections, pp. 1-2; for the application of these concepts in archaeology and Egyptology, see Jensen and Matić, “Introduction: Why do We Need Archaeologies of Gender and Violence, and Why Now?,” pp. 1-23; Matić, “Traditionally Unharmed? Women and Children in NK Battle Scenes,” pp. 245-60; Matić, Body and Frames of War, pp. 139-48; Matić, Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. ↩︎

-

For example, see Kuhrt, “Women and War,” pp. 1-25. ↩︎

-

Matić, “Die ''römische'' Feinde in der meroitischen Kunst,” pp. 251-62; Spalinger, The Persistence of Memory in Kush; Spalinger, Leadership under Fire, pp. 201-42; Wöß, “The Representations of Captives and Enemies in Meroitic Art,” pp. 585-600. ↩︎

-

Matić, “Her Striking but Cold Beauty: Gender and Violence in Depictions of Queen Nefertiti Smiting the Enemies,” pp. 103-21; Matić, “Traditionally Unharmed? Women and Children in NK Battle Scenes,” pp. 245-60; Matić, Body and Frames of War in New Kingdom Egypt, pp. 139-48; Matić, Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. ↩︎

-

Butler, Frames of War, pp. 1-10. ↩︎

-

Butler, Frames of War, p. 26. ↩︎

-

Butler, Frames of War, p. 65. ↩︎

-

Butler, The Force of Non-Violence, p. 6. ↩︎

-

Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” ↩︎

-

Matić, “The Best of the Booty of His Majesty: Evidence for Foreign Child Labor in New Kingdom Egypt,” pp. 53-63; Matić, “Begehrte Beute. Fremde Frauen als Raubgut im Alten Ägypten,” pp. 15-8. ↩︎

-

The author is currently working on a comprehensive study of the ancient Egyptian and Nubian lists of spoils of war from the Egyptian Early Dynastic to Nubian Meroitic period, Matić, “Pharaonic Plunder Economy”. ↩︎

-

Macadam, The Temples of Kawa I. Text, p. 9; Macadam, The Temples of Kawa I. Plates, Pls. 5-6. ↩︎

-

Macadam. The Temples of Kawa I. Text, p. 36; Macadam, The Temples of Kawa I. Plates, Pls. 11-12; FHN I, pp. 172-73. ↩︎

-

Redford, “Taharqa in Western Asia and Libya,” p. 190. The stela actually does not bear the name of Taharqa and Jean Revez attributed it to an entirely different dynasty, Revez, “Une stèle inédite de la Troisième Période Intermédiaire à Karnak: une guerre civile en Thébaïde?”. ↩︎

-

Pope, The Double Kingdom under Taharqo, 98-106. ↩︎

-

Macadam, The Temples of Kawa I. Plates, Pl. 15; FHN I, p. 222. ↩︎

-

For appointing prisoners of war to temples and temple workshops in New Kingdom Egypt, see Matić, “The Best of the Booty of His Majesty: Evidence for Foreign Child Labor in New Kingdom Egypt,” pp. 53-63. ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 447. ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 449. ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 487; Peust, Das Napatanische, p. 40. ↩︎

-

Pope, The Double Kingdom under Taharqo, p. 105. ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 488. ↩︎

-

It is also possible that some of them ended up enslaved in the Mediterranean world, Burstein, “The Nubian Slave Trade in Antiquity: A Suggestion.” ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 489. ↩︎

-

FHN II, pp. 489-90. ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 490. ↩︎

-

FHN II, 491. ↩︎

-

Török, “Sacred Landscape, Historical Identity and Memory,” p. 161; For the same practice in ancient Egypt, at least until the New Kingdom, see Matić, “The Best of the Booty of His Majesty: Evidence for Foreign Child Labor in New Kingdom Egypt,” pp. 53-63. ↩︎

-

FHN II, pp. 722-3; The connection to the conflict with Rome has been challenged since, Zach, “A Remark on the ‘Akinidad’ Stela REM 1003 (British Museum EA 1650),” p. 148. ↩︎

-

Rilly, “New Advances in the Understanding of Royal Meroitic Inscriptions”; Rilly, “Meroitische Texte aus Naga”; Rilly, “Fragments of the Meroitic Report of the War Between Rome and Meroe.” ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, p. 209; see also Török, Meroe City, p. 104. ↩︎

-

Török, Meroe City, p. 104. ↩︎

-

Török, The Kingdom of Kush, p. 401; Török, The Image of the Ordered World, pp. 219-20. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, p. 262. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1; Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 2b. ↩︎

-

He adds that the archaizing iconography and style of the war reliefs of the south and north walls of M250 were based on 25th dynasty Kushite monuments, and supposes that this archaizing iconography was mediated by the early temple at the site, which was built during Aspelta’s reign, and whose reliefs could have been copied on M250, Török, The Image of the Ordered World, p. 213. The 25th dynasty connections are seen, for example, in the motif of spearing the enemy using a lance by piercing the enemy almost horizontally from above-fragments 809, 876, 828, 808, 857, 836, 916, 917, 928, Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 2b. This motif is known from the Amun temple at Gebel Barkal B500, from the reign of Piye, Spalinger, “Notes on the Military in Egypt during the XXVth Dynasty,” p. 48, Figs. 3 and 4. ↩︎

-

Wenig, Africa in Antiquity, pp. 59-60. ↩︎

-

Hofmann, “Notizen zu den Kampfszenen am sogenannten Sonnentempel von Meroe,” pp. 519-21. ↩︎

-

Chapman and Dunham, Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal, Pl. 17. ↩︎

-

Shinnie and Bradley, “The Murals from the Augustus Temple, Meroe,” p. 168, Fig. 1; Matić, “Der Kopf einer Augustus-Statue aus Meroe,” p. 70, Abb. 7. ↩︎

-

Wöß, “The Representations of Captives and Enemies in Meroitic Art,” p. 589. ↩︎

-

Lohwasser, “Kush and her Neighbours beyond the Nile Valley In The Fourth Cataract and Beyond,” p. 131. ↩︎

-

FHN III, p. 831; Jones, Strabo. The Geography Vol. VIII, p. 139. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, pp. 189-90. ↩︎

-

Minas-Nerpel and Pfeiffer, “Establishing Roman Rule in Egypt: The Trilingual Stela of C. Cornelius Gallus from Philae,” pp. 285-8. ↩︎

-

Kormysheva, “Political Relations between the Roman Empire,” p. 306; Török, Between the Two Worlds, pp. 434-6. ↩︎

-

Jameson, “Chronology of the Campaigns of Aelius Gallus and C. Petronius,” p. 77; Török, Between the Two Worlds, p. 441. ↩︎

-

Török, The Kingdom of Kush, p. 449; Török, Between the Two Worlds, p. 441. ↩︎

-

Török, Meroe City, p. 185. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, p. 142. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, p. 139. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, pp. 140-1, Abb. 39, 40, 41, 42; p. 257, Abb. 95. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, p. 140, Abb. 38; p. 257, Abb. 95. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 2b, C10. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 2b, C10. ↩︎

-

For example, in tribute scenes from the tombs of Useramun-TT 131, Rekhmire-TT 100, Horemhab-TT 78 but also the Beit el-Wali temple of Ramesses II, Matić, “Children on the Move: ms.w wr.w in the New Kingdom Procession Scenes.” pp. 378-9, Fig. 12. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, p. 189. ↩︎

-

FHN III, p. 831; Jones, Strabo. The Geography Vol. VIII, p. 139. ↩︎

-

Hinkel, Der Tempelkomplex Meroe 250. I. 1, pp. 138-9, Abb. 37b. ↩︎

-

Török, The Image of the Ordered World, p. 220; Breyer, Einführung in die Meroitistik, p. 67. ↩︎

-

FHN III, p. 831; Jones, Strabo. The Geography Vol. VIII, p. 139. ↩︎

-

Rilly and De Voogt, The Meroitic Language and Writing System, p. 185. ↩︎

-

Rilly, “Meroitische Texte aus Naga,” p. 190; Matić, “Die ''römische'' Feinde in der meroitischen Kunst,” p. 258. ↩︎

-

Matić, “Traditionally Unharmed? Women and Children in NK Battle Scenes,” pp. 245-60; Matić, Body and Frames of War in New Kingdom Egypt, pp. 139-48. ↩︎

-

Strathern, Before and After Gender, p. 21. ↩︎

-

Parkinson, “Homosexual’ Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature”; Matić, Body and Frames of War, pp. 139-48; Matić, Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. ↩︎

-

Grimal, La Stèle Triomphale, p. 177; FHN I, p. 111. ↩︎

-

Grimal, La Stèle Triomphale, p. 176. ↩︎

-

Goedicke, Pi(ankhy) in Egypt, p. 172. ↩︎

-

Ritner, The Libyan Anarchy, p. 492. ↩︎

-

El Hawary, Wortschöpfung, p. 243. ↩︎

-

O’Connor and Quirke, “Introduction: Mapping the Unknown in Ancient Egypt,” p. 18. ↩︎

-

For a detailed analysis see Lavik, A People Tall and Smooth-Skinned. ↩︎

-

El Hawary, Wortschöpfung, p. 281. ↩︎

-

Ritner, The Libyan Anarchy. pp. 477 and 490. ↩︎

-

Dieleman, “Fear of Women?,” p. 14. ↩︎

-

FHN I, p. 84. ↩︎

-

Karlsson, “Gender and Kushite State Ideology.” ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 450. ↩︎

-

Matić, Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. ↩︎

-

FHN II, p. 653. ↩︎

-

FHN III, p. 816. ↩︎

-

FHN III, p. 831; Jones, Strabo. The Geography Vol. VIII, p. 139. ↩︎

-

Lohwasser, “The Role and Status of Royal Women in Kush,” p. 64; Lohwasser and Philipps, “Women in Ancient Kush,” p. 1021. ↩︎

-

McCoskey, “Gender at the Crossroads of Empire”. pp. 61-8. ↩︎

-

Wilkins, Barnard, and Rose, “Roman Artillery Balls from Qasr Ibrim, Egypt,” pp. 71 and 75, Pl. 8, 4F. ↩︎

-

Hall, The Pharaoh Smites His Enemy, p. 44. ↩︎

-

Queen Tiye (ca. 1398-1338 BCE) of the 18th Dynasty is depicted trampling over enemies in the guise of a female sphinx. Queen Nefertiti (ca. 1370-? BCE) of the same dynasty is depicted both smiting enemies and trampling over them in the guise of a sphinx. I argued that we can observe a clear gender structure behind such images, and that the status of queens smiting enemies is lower than the status of the king smiting male enemies, Matić, “Her Striking but Cold Beauty: Gender and Violence in Depictions of Queen Nefertiti Smiting the Enemies,” pp. 103-21. ↩︎

-

Matić, “Her Striking but Cold Beauty: Gender and Violence in Depictions of Queen Nefertiti Smiting the Enemies,” pp. 103-21; Matić, “Traditionally Unharmed? Women and Children in NK Battle Scenes,” pp. 245-60; Matić, Body and Frames of War in New Kingdom Egypt, pp. 139-48. ↩︎

-

Williamson, “Alone before the God: Gender, Status, and Nefertiti’s Image,” pp. 179-92. ↩︎

-

Matić, Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. ↩︎

-

Chapman and Dunham, Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal, Pl. 17. ↩︎

-

Rilly, “Meroitische Texte aus Naga,” Abb. 218. ↩︎

-

Chapman and Dunham, Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal, Pl. 7A. ↩︎

-

Chapman and Dunham, Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroë and Barkal, Pls. 18B and 18D. ↩︎

-

Gamer-Wallert, Der Löwentempel von Naqa in der Butana (Sudan) III, Bl. 1-2. ↩︎

-

Pomerantseva, “The View on Meroitic Kings and Queens as it is Reflected in their Iconography,” p. 625. ↩︎

-

Phillips, “Women in Ancient Nubia,” p. 292. ↩︎

-

Matić, “Her Striking but Cold Beauty: Gender and Violence in Depictions of Queen Nefertiti Smiting the Enemies,” pp. 116-7. ↩︎

-

For exceptionality and the possible divinization of Amanirenas (1st century CE), see Zach, “A Remark on the ‘Akinidad’ Stela REM 1003 (British Museum EA 1650),” p. 149. ↩︎

-

Matić, “Pharaonic Plunder Economy.” ↩︎

-

Matić, Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. ↩︎

-

For weapons in female burials of the Kerma period interpreted as symbols of status, see Hafsaas-Tsakos, “Edges of Bronze and Expressions of Masculinity,” p. 89. Henriette Hafsaas has in personal communication informed me that she considers investigating this topic further and maybe revising her conclusions. ↩︎

-

For the military activities of Ahhotep and Hatshepsut see, Matić, Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt; Taterka, “Military expeditions of King Hatshepsut,” pp. 90-106. ↩︎